Australian musicologist Angharad Davis leads her original piece “Radiance” at the heart of the hollow square during the new edition of The Sacred Harp.

Lucy Grindon

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Grindon

This September, over 700 vocalists gathered in Atlanta to honor the release of the newest edition of a historic Christian music collection deeply rooted in American tradition.

The Sacred Harp, originally published in 1844, features hymns and anthems written using “shape notes” – a unique notation system that simplifies sight-reading by assigning distinct shapes to musical syllables. Instead of conventional notes, singers read triangles, circles, squares, and diamonds, each representing the syllables fa, sol, la, or mi, which correspond to specific pitches.

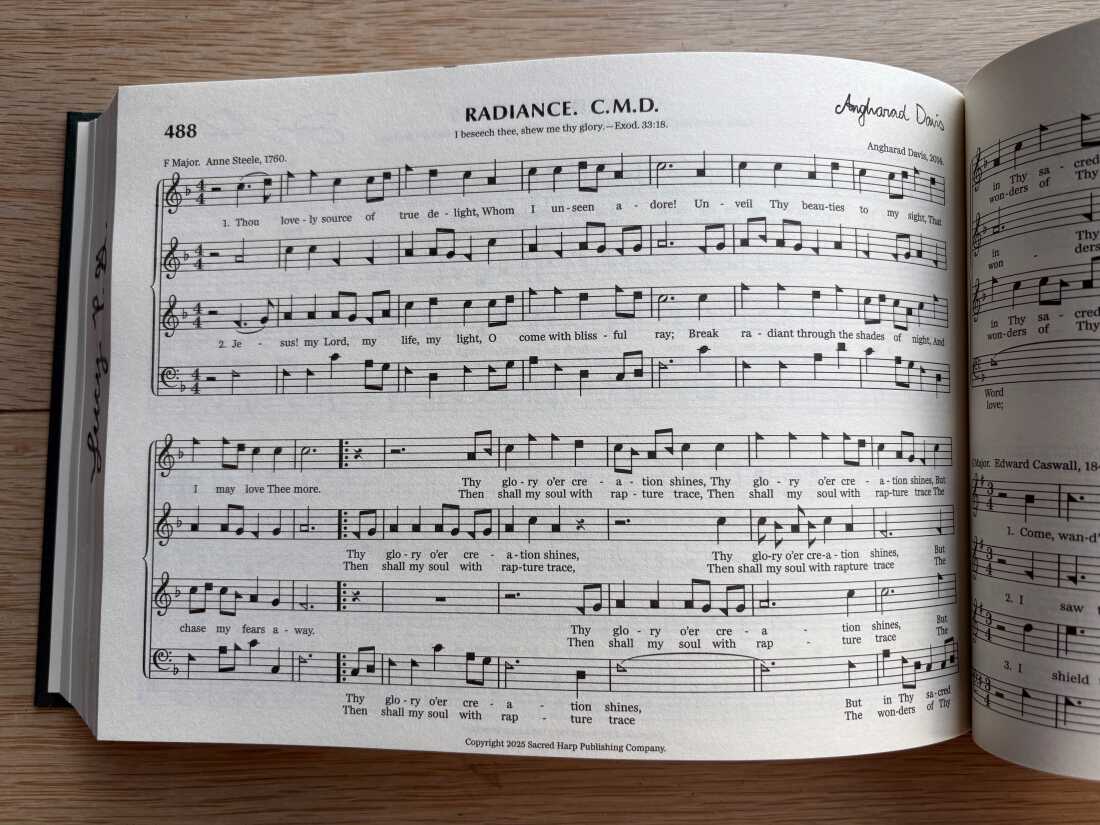

The composition “Radiance” by Angharad Davis appears on page 488 of the updated songbook.

Lucy Grindon

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Grindon

This year’s convention marked the largest Sacred Harp singing event in recent memory, celebrating the culmination of seven years dedicated to revising the songbook. Attendees traveled from far and wide to perform 113 newly added pieces.

“This gathering is a once-in-a-lifetime experience for many of us,” shared Sydney-based composer Angharad Davis.

Leigh Cooper of San Francisco distributes the freshly printed 2025 edition of The Sacred Harp to attendees at the convention’s entrance.

Lucy Grindon

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Grindon

While Sacred Harp singing has its roots in the American South, this event attracted participants from 35 U.S. states, three Canadian provinces, and countries including Australia, the UK, Ireland, and Germany. Singers arranged themselves into tenor, treble, alto, and bass groups, performing a cappella. Alto singer Lucy O’Leary emphasized that the “Sacred Harp” refers to the human voice itself.

The repertoire is deeply Christian, often reflecting on themes of mortality. For instance, the hymn “Hallelujah,” penned in 1759, includes the lines: “And let this feeble body fail, / And let it faint or die; / My soul shall quit this mournful vale, / And soar to worlds on high.”

Notably, no single denomination governs Sacred Harp singing. People from diverse backgrounds-Baptists, Quakers, Catholics, Episcopalians, Mennonites, atheists, and others-join together in song, welcoming all who wish to participate.

Over nearly 200 years, each generation has refreshed the songbook, which now features works by 49 living composers, a significant increase from just five before this latest update.

However, when the previous revision was completed in 1991, the tradition’s future seemed uncertain.

Judy Hauff, a composer of four songs in the collection, first encountered Sacred Harp in the mid-1980s. At that time, most singers were elderly, she recalled during the convention.

“I would listen to the powerful voices of these senior singers and wonder what it must have sounded like when they were young adults,” Hauff reflected.

Back then, she doubted she would ever witness a revival.

“We never imagined a gathering like this,” Hauff said emotionally, gesturing to the crowd that included hundreds of singers under 50, with hair colors ranging from black and brown to blonde and even purple.

Lauren Bock from Atlanta, who contributed three songs to the new edition and served on the nine-member revision committee, attributes the surge in younger participants partly to the 2003 film Cold Mountain, which featured Sacred Harp singing, as well as the influence of YouTube.

The demographic shift also brought greater diversity, welcoming more people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and those without religious affiliations.

The new composers mirror this evolving community. José Camacho-Cerna, a 27-year-old from Valdosta, Georgia, is the first Latino composer included in the book.

“I used to play in a punk band, which might sound odd, but that’s part of what drew me to Sacred Harp-it felt like 19th-century metal music,” he explained.

Camacho-Cerna, who is engaged to a man, is also among the first openly LGBTQ+ composers featured.

José Camacho-Cerna of Valdosta, Georgia conducts his piece “Lowndes” at the center of the hollow square during The Sacred Harp event.

Lucy Grindon

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Grindon

Raised in a Pentecostal church that rejected LGBTQ+ identities, Camacho-Cerna was surprised to find acceptance at his first Sacred Harp singings at age 19. He soon realized that the community prioritized the music above all else, regardless of personal backgrounds, which empowered him to embrace his true self openly.

“Sacred Harp gave me the courage to stop hiding and be authentic,” he said.

At the convention, composers took turns leading their own songs from the center of the square, using arm movements to keep rhythm. Camacho-Cerna’s composition “Lowndes,” inspired by his grandfather’s passing in Honduras, was performed for the first time in full, an experience he described as transformative.

“It was a moment I’ll never forget. I feel like I’ve left a meaningful legacy,” he shared.

Deidra Montgomery from Providence, Rhode Island, the first Black composer featured in the book, began crafting their song “Mechanicville” in 2010.

“Leading my piece among a vast group of singers, coordinating the fugue sections, and seeing familiar faces from my journey as a singer was exhilarating,” Montgomery said.

Micah Walter signs his song “Revere” for a fellow participant.

Lucy Grindon

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Grindon

During breaks, attendees eagerly sought autographs from the composers.

Lauren Bock noted that increasing diversity among composers was not a deliberate aim for the new edition. The revision committee evaluated submissions anonymously, and the resulting roster naturally reflects the current singing community.

“Those who contributed songs are active singers today, and they differ significantly from the 1991 generation,” Bock explained.

On the event’s second day, Bock’s 8-year-old daughter, Lucey Karlsberg, led the hymn “Hallelujah” alongside other children.

Jesse Karlsberg leads a Sacred Harp hymn at the gravesite of Benjamin Franklin White, the original compiler of the 1844 edition of The Sacred Harp, located in Atlanta’s historic Oakland Cemetery.

Lucy Grindon

hide caption

toggle caption

Lucy Grindon

Later, Karlsberg joined others in singing at the grave of Benjamin Franklin White, who originally compiled the songbook. When the next revision is published, Karlsberg will likely be in her 40s and is already determined to contribute a song herself. “I absolutely will!” she declared enthusiastically.