Communities neighboring Turkish-operated quarries in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, report enduring constant hazards from falling rocks, pervasive dust clouds, and sudden, loud explosions at all hours.

On the afternoon of September 24, 2024, Dorathy Ushiya sat on the porch of her modest one-room home in Dutse Bmuko, a small settlement near Abuja. Next to her were bottles of kunun aya, a traditional tiger nut beverage she sells to locals. As she conversed with a neighbor, she kept watch for potential buyers, knowing that even a few sales could mean feeding her toddler that day.

Without warning, a deafening blast erupted, akin to an explosion. Fragments of stone and debris flew violently, striking her face and eyes. She fell to the ground, blinded and in agony. Her neighbor rushed her to a local clinic, but her injuries required specialist care. For a week, she returned daily for treatment, unable to work, with her eyes remaining inflamed and painful for months.

“I almost lost my sight,” Ushiya recounted.

The blast’s impact extended beyond her injuries. Rocks and rubble damaged her roof and those of nearby homes. “People fled in panic, while others lay flat on the road to avoid the flying stones,” she said.

This explosion originated from a granite quarry operated by Istanbul Concrete, located just a few hundred meters from the village. After Ushiya lodged a complaint, the company agreed to cover her medical expenses and paid a meager 20,000 naira (about €11) in compensation-an amount insufficient to cover lost income or home repairs.

Such incidents are not rare. In 2023, residents reported a 50-kilogram rock blasted from the quarry crashing through a pregnant woman’s house, landing on her bed-luckily, she was not inside at the time.

Dutse Bmuko is not alone in facing these challenges. A few miles northwest, in Kubwa, another granite quarry operates, with a third located 250 kilometers north near Kaduna in Zagina. The latter two are owned by Zeberced Limited, while the Dutse Bmuko quarry is managed by Istanbul Concrete but owned by Chief Cornerstone Investments.

All three quarries are situated dangerously close to rural communities. Our visits revealed residents and workers enduring daily explosions, dust pollution, and neglect that jeopardizes their health and safety.

Both companies are controlled by the Kurt family from Turkey, who entered Nigeria’s market nearly twenty years ago and have since diversified into construction, furniture, and industrial parks. Their ventures have received endorsements from Nigerian governments and even the UK Conservative Party. The Kurts’ success may also be linked to associations with the Gülen movement, which had a significant presence in Abuja.

While these firms generate tens of millions of dollars annually, enriching their owners, the communities nearby live amid constant hazards-debris, dust, and noise-that make daily life unbearable.

Drone image of Kubwa. Photo credit: Solomon Shaibu.

Living Amid the Quarries

Dutse Bmuko is a community predominantly inhabited by low-income families. Until recently, it lacked electricity and basic infrastructure. The main road remains unpaved and without drainage, and there is no public water supply; residents rely on boreholes and rainwater collection.

However, Istanbul Concrete’s quarrying activities have contaminated rainwater sources, rendering them unsafe. Dust from blasting and machinery coats everything in a thick layer. The unpaved road is deteriorating under the constant traffic of heavy trucks transporting crushed stone-the very material that could repair the roads. These trucks frequently block access to schools and markets. In 2018, a Zeberced truck driver caused a fatal accident on the Abuja road, killing a deaconess; he was charged with reckless driving and manslaughter but evaded bail for two years.

Residents near the quarry always carry masks to protect against dust, and white clothing is avoided as it stains instantly. Explosions can occur unpredictably, day or night.

Ushiya’s neighbor, Audu Sulaiman, noted that the company often fails to provide the legally required 48-hour notice before blasting, leaving the community anxious and on edge. Midnight detonations frequently wake him, and his children suffer from respiratory problems aggravated by dust exposure. On windy days, they must wear masks even outdoors. “You can’t even sit on your porch to eat without being covered in dust,” he lamented.

In Kubwa, Zeberced runs what is reportedly West Africa’s largest quarry, sprawling over three million square meters of hillside. The constant blasts shake the ground, and flying stones damage homes bordering the site.

Farakwai, near Kaduna, hosts Zeberced’s third quarry. Here, heavy trucks rumble along unpaved roads connecting the mine to villages like Zagina and Tudun-Kaya. Dust clouds envelop homes-many made of fragile mud bricks-and even a nearby children’s playground. When blasts occur, children rush indoors for safety.

Establishing Roots in Nigeria

Founded in 2007 by Turkish brothers Adil Aydın Kurt and Cemal Kurt, Zeberced Limited has grown significantly. Adil, a Turkish national with UK ties and a Caribbean passport, portrays himself as a self-made entrepreneur who sought new business opportunities during the 2007 global financial crisis. After considering Central Asian countries, he settled on Abuja, impressed by its development and organization.

Starting from humble beginnings-a rock-crushing operation under a mango tree-Zeberced has expanded into one of West Africa’s largest quarry operators.

In 2011, during a Nigerian presidential delegation visit to Turkey, Kurt accompanied officials to industrial zones, expressing ambitions to replicate such projects in Nigeria. Shortly after, he secured 250 hectares for the Abuja Industrial Park, a $144 million flagship development supported by Nigerian officials. That same year, Zeberced was contracted to build the new Turkish embassy in Abuja.

Turkey’s growing influence in sub-Saharan Africa coincided with the Gülen movement’s strong presence in Abuja, which established schools, health centers, and trade associations, fostering economic and cultural ties. Though later accused of misappropriating funds, the movement’s legacy continues through its US-based charity.

Despite political upheavals in Turkey and the movement’s designation as a terrorist organization by Ankara after the 2016 coup attempt, its Nigerian institutions remain active, with the Nigerian government resisting Turkish pressure to shut them down.

While no direct links between the Kurt family and the Gülen movement are confirmed, there are indications of affinity. Özlem Kurt, Adil’s wife and a Zeberced UK director, has publicly supported the movement, and their daughter attended a Gülen-affiliated school.

The Kurts have maintained a robust presence in Nigeria, expanding into various sectors and establishing UK-based holding companies that emphasize British involvement in Nigerian ventures, supported by the UK government, particularly in Commonwealth countries.

The Gündoğdu family, another Turkish clan, is closely connected to Zeberced’s operations, managing furniture companies and co-directing Istanbul Concrete. Yakup Gündoğdu’s marriage to Meram Indimi, daughter of Nigerian oil magnate Mohammed Indimi, further cements ties with Nigeria’s elite.

Adil Kurt denies reliance on government contracts but enjoys high-level political backing. In 2023, he met Nigeria’s Vice President Kashim Shettima, who praised Zeberced’s infrastructure contributions and job creation plans, including a projected 40,000 direct jobs at the Abuja Industrial Park. However, public feedback on social media highlights community grievances over dust, road damage, and health impacts.

In 2024, UK Business Secretary Kemi Badenoch attended the Abuja Industrial Park’s groundbreaking, marking a new trade partnership between Nigeria and the UK. The park’s $144 million cost remains opaque, with the UK Department for Business and Trade denying involvement in its financing.

Financial transparency is lacking. An Abuja Community study estimated that Zeberced and Istanbul Concrete extract between 12,000 and 20,000 tonnes of granite daily, generating revenues of ₦72 million to ₦120 million ($47,000 to $78,000) per day. In 2023, Zeberced reportedly paid ₦3.89 billion ($6.6 million) in taxes and royalties. These figures suggest substantial profits at the expense of local communities.

Regulatory Violations and Unfulfilled Promises

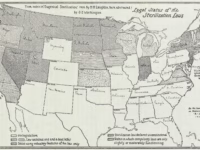

Nigeria’s 2013 National Environmental (Quarrying and Blasting Operations) Regulations prohibit quarrying within three kilometers of residential or commercial zones. Zeberced claims no residences existed within this radius at the time of their Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). However, drone and satellite imagery reveal homes adjacent to both Zeberced’s Kubwa quarry and Istanbul Concrete’s Dutse Bmuko site, predating quarry operations.

Many residents, including Chief Hassan Shakpara’s family, have lived in Dutse Bmuko for generations, confirming the presence of homes before quarrying began in 2011. The area has since become more densely populated.

A former Zeberced blast intern disclosed that detonations occur up to six days a week, weakening nearby structures. Some homes lie as close as 1.5 kilometers from blasting sites, near a major market.

Human rights lawyer Festus Ogun criticized regulatory bodies like the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency and the Ministry of Environment for inadequate enforcement, calling for license suspensions and prosecutions of company officials for criminal violations.

Community Development Agreements (CDAs) were required for quarry approval. Dutse Bmuko’s agreement with Chief Cornerstone Investments promised classrooms, granite supplies, local employment, and an ambulance. Chief Hassan reports only a primary school was built, with no lasting jobs created. Employment is limited to casual roles like cleaning and security, despite qualified locals.

The CDA mandates safety precautions during blasting, including alarms and evacuation warnings. Zeberced’s Kubwa quarry operates under a similar agreement, currently under renewal. The company asserts blasting occurs only on Mondays with prior notifications, yet unannounced blasts were observed during our visit, causing property vibrations and community distress.

In Farakwai, Zeberced’s community agreement covers Zagina village but excludes neighboring Tudun-Kaya, which suffers from dust and noise pollution. Locals describe this as a “divide and rule” tactic. The agreement includes promises of jobs, a school, mosque, and scholarships, but many projects remain incomplete, and boreholes were abandoned.

Alhaji Yinusa Yusha’u of the Zagina community development committee beside an abandoned borehole. Photo credit: Justice Nwafor.

The Human and Environmental Cost

Residents in Tudun-Kaya report severe health consequences, including fatalities. Farmer Ahmed Abubakar lost his wife to chronic asthma, worsened by poor air quality. His two sons now exhibit similar symptoms, with limited access to medical care.

Ahmed Abubarkar and his family. Photo credit: Justice Nwafor.

In Dutse Bmuko, Juliet Ugwu’s health declined shortly after moving in, experiencing breathing difficulties and eye irritation from dust. She temporarily relocated to escape the conditions and plans to leave once her lease ends, doubting the community’s prospects for a healthy life.

Public health expert Dr. Golibe Ugochukwu explains that prolonged exposure to dust and pollution leads to respiratory illnesses such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and increased susceptibility to tuberculosis. Noise pollution from blasts and heavy vehicles also risks hearing loss and psychological distress.

Efforts to obtain environmental impact assessments from regulatory agencies have been unsuccessful. Zeberced claims its assessments are thorough, monitored, and publicly available. Independent studies reveal homes less than 50 meters from quarries, noise levels exceeding residential limits, and widespread structural damage.

Air quality measurements in early 2024 showed particulate matter (PM10) levels exceeding World Health Organization (WHO) limits, with PM2.5 levels more than double the safe threshold. These pollutants are linked to serious health risks, including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

Zeberced acknowledges reports of health issues but insists it complies with legal dust limits and employs suppression techniques like road watering and pre-blast wetting. The company welcomes third-party reviews and dialogue with affected communities.

Safety Concerns and Labor Issues

Despite promises of local employment, the quarries often hire workers from other Nigerian regions or Turkey. A former intern described a workplace divided along ethnic lines, with Turkish management frequently shouting at Nigerian laborers, many of whom struggle with language barriers. This communication gap in a hazardous environment increases risks.

Workers report long hours for minimal pay, with inadequate provision of protective gear such as masks, goggles, and boots, which they often must purchase themselves. Chemical odors and unsafe handling of explosives are common, with some employees working barefoot or in flip-flops. “They don’t care about safety,” one operator said.

The intern expressed reluctance to work for the company again, citing poor treatment and cultural disconnects.

Zeberced claims only 50 of its 2,000 employees are foreign, but does not specify their roles. The company and officials tout the creation of 40,000 jobs at the Abuja Industrial Park, yet only about 1,000 positions have been filled so far.

Community Resistance and Legal Challenges

Local protests against quarry operations have been met with police repression, including teargas in Kubwa. In Kaduna, community leaders report intimidation to silence criticism. Legal actions have had limited effect; a 2019 court injunction temporarily halting Zeberced’s activities was ignored by the company, which denies knowledge of any such orders.

Residents express despair and fear, with some attributing damage to their homes to blasting and feeling powerless against the company’s influence.

Cracks in walls of a home in Kubwa. Photo credit: Justice Nwafor.

Corporate Image vs. Reality

Since its inception, Zeberced has portrayed itself as a nation-building enterprise, investing in infrastructure and community projects. High-ranking officials, including ministers and the vice president, have publicly lauded the company, which maintains close media relations. However, many promised community developments remain incomplete or abandoned, and parliamentary scrutiny of the company’s practices is underway.

In March, Nigeria’s parliament voiced concerns over Zeberced’s detrimental effects on Kubwa’s communities, citing violations of mining and environmental laws, health complaints, property damage, and psychological harm. Lawmakers called for investigations that could revoke the company’s licenses and questioned the cost and quality of its infrastructure projects.

As of mid-2024, no official update on investigations has been released. Istanbul Concrete has not responded to inquiries.