BERLIN – On a gray September afternoon, I cycled through the bustling streets of Germany’s capital to attend the annual political gathering of the VDMA, the Association of German Mechanical and Plant Engineering. This influential body represents thousands of German manufacturers specializing in industrial machinery and equipment, many of which belong to the renowned “Mittelstand” – the small and medium-sized enterprises often hailed as the backbone of Germany’s economy.

The VDMA wields significant influence in political circles, and its yearly summit has become a pivotal event for German policymakers. Just a day prior, Chancellor Friedrich Merz addressed the assembly, where the VDMA president voiced the sector’s frustration, describing the current state of German manufacturing as “disheartening and infuriating.”

“Nearly every key indicator is trending downward,” Oliver Richtberg, head of the VDMA’s Foreign Trade Department, confided during our meeting. Exports are plummeting, layoffs and furloughs are increasing, and production has shrunk by 4.5 percent in just the last half-year. This decline is part of a prolonged downturn, prompting the VDMA to sound urgent warnings for transformative action.

Germany is grappling with a profound economic challenge.

For over five years, economic expansion has stalled, and the country’s celebrated manufacturing sector is under severe strain. Multiple factors contribute to this crisis, including soaring energy costs following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the repercussions of American tariffs.

Yet, an even more formidable disruption is emerging-one that echoes the early 2000s experience in the United States but poses an even greater threat to Europe’s largest economy.

Economists have dubbed this phenomenon the “second China Shock.” The original China Shock occurred in the early 2000s when China’s export surge overwhelmed global manufacturers, leading to massive job losses and economic distress in industrial regions, particularly in the U.S. This upheaval is widely believed to have fueled a populist political backlash that continues to influence American politics today.

Unlike the U.S., Germany largely weathered the first China Shock unscathed. However, experts now warn that the second China Shock is shaking the very core of Germany’s export-driven industrial economy.

“This is a crisis of existential proportions for Germany,” explains Dalia Marin, an economist at the Technical University of Munich. She warns that the current wave of disruption could trigger a “deindustrialization” far more severe than what the U.S. endured during the initial China Shock.

What shielded Germany during the first wave? What exactly defines this second shock? And why does it threaten to be so devastating?

How Germany avoided the brunt of the first China Shock

When China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, it accelerated its industrial growth, flooding global markets with inexpensive goods. Economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson later coined this phenomenon the “China Shock,” which devastated manufacturing sectors worldwide, especially in the U.S.

Germany, however, was largely shielded from this initial wave.

Sander Tordoir, an economist at the Centre for European Reform, attributes this to the nature of China’s early export boom, which focused on low-cost products such as textiles, toys, consumer electronics, and furniture-sectors that differ significantly from Germany’s core industries like automotive, chemicals, and machinery.

Jens Südekum, an economics professor at Düsseldorf University and advisor to the German finance minister, notes that while some low-end sectors like shoemaking were affected, these represented only a small fraction of Germany’s industrial base.

In fact, Germany’s manufacturing sector benefited from China’s growth. As China built vast new factories, it required sophisticated industrial machinery-precisely the kind German companies excel at producing.

“Post-WTO accession, German machinery firms and China formed a symbiotic relationship,” Richtberg explains. “We profited immensely from China’s industrial expansion.”

Moreover, China’s emerging middle and upper classes developed a strong preference for German automobiles, boosting sales for brands like Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW.

During the early 2000s, Germany also implemented labor reforms that lowered unemployment and enhanced competitiveness. The integration of former Eastern Bloc countries into the EU further expanded markets and optimized supply chains for German manufacturers.

Additionally, the adoption of the euro, shared with several weaker economies, sometimes resulted in a relatively undervalued currency for Germany, making its exports more affordable internationally, especially during crises like the European debt turmoil.

Compared to other Western nations whose manufacturing sectors contracted under Chinese competition, Germany stood out as an exception, partly due to fortunate alignment between its industrial strengths and China’s demands.

By 2012, exports to China accounted for nearly 3% of Germany’s GDP-a substantial figure compared to the U.S., where exports to China have never exceeded 1% of GDP.

What sets the second China Shock apart

Today, economists warn of a new wave-the second China Shock-driven largely by China’s efforts to counteract its domestic economic slowdown following the real estate bubble burst around 2021. Since then, Chinese exports have surged dramatically.

Unlike the first shock, this time China is competing directly in Germany’s core industries. Chinese firms have advanced rapidly in sectors such as machinery, electronics, and automotive manufacturing, eroding demand for German products both domestically and globally.

Once one of Germany’s largest customers, China has transformed into a formidable rival.

The scale of this shift is striking. In 2019, China was a net importer of passenger vehicles, bringing in about one million more cars than it exported. By 2023, it had become the world’s leading car exporter, shipping roughly five million more vehicles than it imported, largely due to breakthroughs in electric vehicle production.

This transformation traces back to China’s 2015 “Made in China 2025” initiative, a decade-long strategy to elevate the country into a global manufacturing leader. Heavy investments in research, development, and industrial policy have propelled China to meet 86% of the plan’s 260 targets, according to a 2024 South China Morning Post analysis.

Chinese companies now design and produce smartphones rivaling iPhones, dominate lithium-ion battery and solar panel manufacturing, and lead in AI and robotics innovation. They are also making significant strides in aircraft, shipbuilding, and electric vehicles-directly challenging German industrial machinery and automotive sectors.

“China’s strength lies in its long-term strategic planning and execution,” Südekum observes. “Their orchestrated shift to electric vehicles has made them a major exporter, reducing reliance on German imports.”

Richtberg recalls that German manufacturers first sensed this shift around 2022-2023, as pandemic travel restrictions lifted and they returned to China to find a dramatically evolved industrial landscape.

Chinese machinery now costs about 30% less than German equivalents. While quality may lag, many customers find these products sufficiently reliable for their needs.

A critical question is how much of China’s competitive advantage stems from unfair practices. Richtberg points to natural benefits such as vast domestic markets, efficient supply chains, long working hours, lower wages, innovation investments, reduced taxes, and lighter regulations.

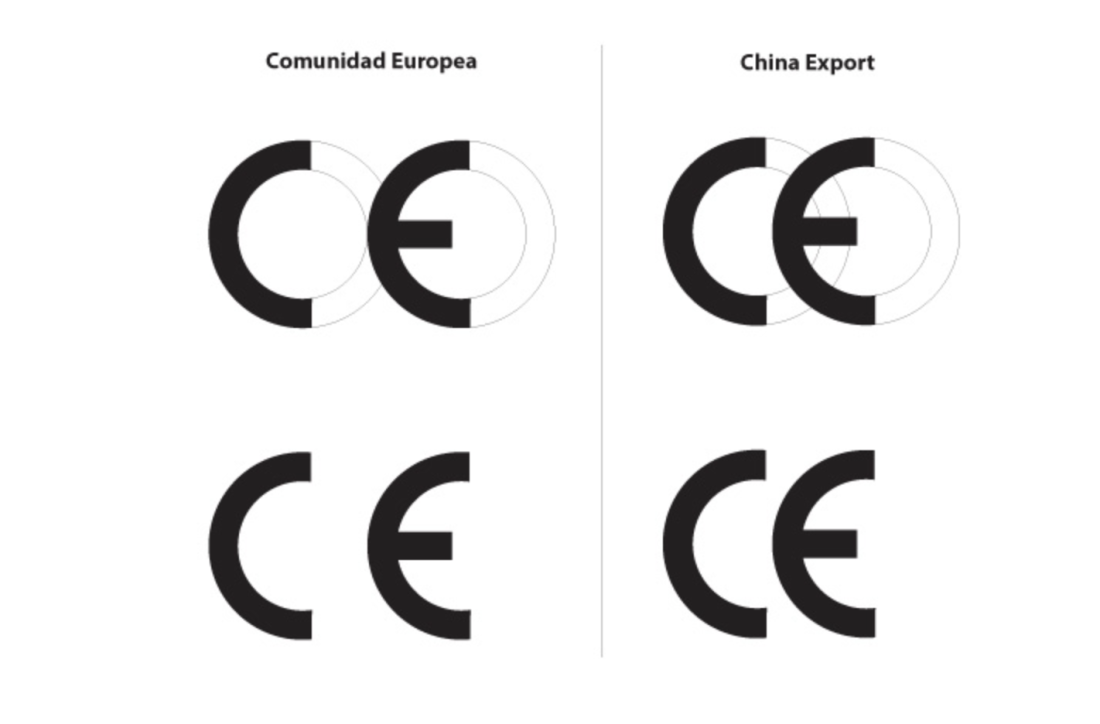

Yet, he also highlights questionable tactics, including regulatory evasion. For instance, European products bear the “CE” mark certifying compliance with health, safety, and environmental standards. Chinese manufacturers mimic this symbol almost identically, misleading buyers about product certification.

More significantly, the Chinese government heavily subsidizes its manufacturers, providing free or inexpensive land, cheap credit, and ongoing support even for unprofitable firms. An IMF study estimates these subsidies amount to about 4% of China’s GDP annually.

Strategies for Germany’s response

For years, the VDMA has urged German and EU authorities to enforce fair competition by pressuring China to adhere to regulations and eliminate distorting subsidies. However, China has largely ignored these calls.

Consequently, the VDMA advocates for tax cuts and deregulation to boost domestic competitiveness and, notably, supports imposing countervailing tariffs on subsidized foreign imports-a stance gaining traction among economists.

Yet, tariffs only shield German firms within the EU. Germany’s heavy reliance on exports-over 42% of GDP in 2024 compared to less than 11% in the U.S.-poses a challenge in competing with China in global markets beyond Europe.

This reliance amplifies the threat of the second China Shock. The first shock mainly affected low-end manufacturing and still caused over a million U.S. job losses. Germany’s manufacturing sector, accounting for about 18% of GDP, is more integral to its economy than America’s.

Moreover, the U.S.’s retreat behind tariff barriers complicates matters. High American tariffs on Chinese goods have led to rerouting, with Chinese exporters increasingly targeting Europe’s less restrictive markets.

Tordoir suggests a potential solution lies in encouraging China to boost domestic consumption, reducing its export dependency-a reform that could benefit all parties.

Germany itself is shifting toward stimulating internal demand. Under Chancellor Merz, constitutional reforms now permit increased government spending, which is being directed toward defense and infrastructure projects.

“Our best path forward is to strengthen domestic and EU-wide demand,” Südekum asserts. He views recent fiscal reforms as a positive start and supports EU initiatives to incentivize consumers to “Buy European.”

Interestingly, some economists recommend that Germany learn from China’s strategic industrial policies. Tordoir emphasizes the value of studying China’s targeted investments and long-term planning, advocating for coordinated EU-wide industrial strategies to bolster key sectors.

Marin expresses concern over Germany’s lag in innovation, particularly in electric vehicles and battery technology. Wolfgang Münchau’s book Kaput: The End of the German Miracle critiques German leadership for clinging to outdated industrial models and failing to invest adequately in emerging technologies. Germany’s digital sector and venture capital landscape remain underdeveloped, and even its iconic automakers have been slow to embrace electrification and software integration.

Marin highlights China’s success in technological advancement through joint ventures that facilitated technology transfer. She proposes that Germany adopt a reverse approach, inviting foreign firms-including Chinese companies-to collaborate in advancing German technological capabilities.