Two rabbits peeking from top hats belonging to Magic Circle illusionist Gus Davenport at London’s Scala Theatre in 1951.

Ron Burton/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

hide caption

toggle caption

Ron Burton/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

Among the topics frequently cited by former President Trump as hoaxes are climate change, the Russiagate investigation, and the Jeffrey Epstein scandal. Yet, history provides us with more straightforward and less politically charged examples: the infamous “missing link” known as the Piltdown Man, the Cottingley Fairies photographs, the exposure of Hitler’s forged personal diaries, and even the curious case of the Balloon Boy.

These instances fall under the umbrella of hoaxes-deceptions, scams, cons, and frauds designed to mislead.

With Halloween approaching, NPR’s Word of the Week explores the intriguing and almost enchanting origins of the word “hoax.”

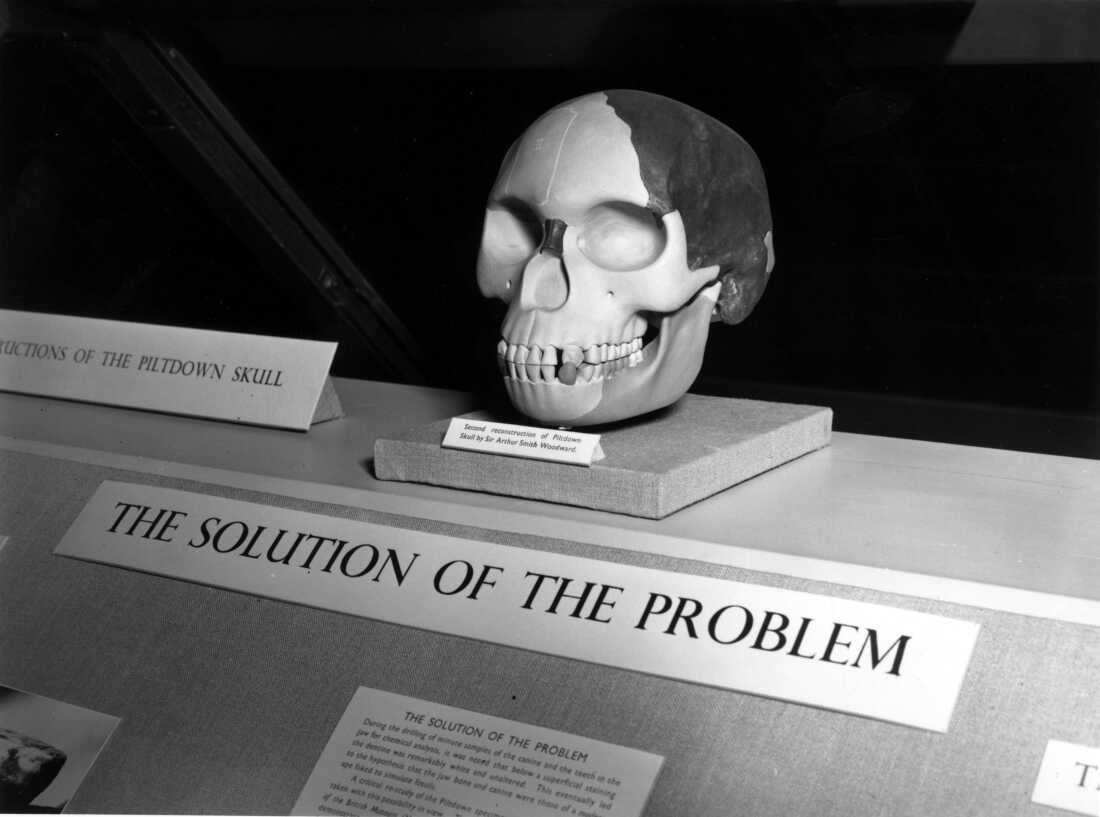

A replica of the Piltdown Skull displayed at London’s Natural History Museum. Initially accepted as proof of the “missing link” between apes and humans after Charles Dawson’s 1912 discovery, it was later unmasked as a hoax, pieced together from a human skull and an orangutan jawbone.

Reg Speller/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

hide caption

toggle caption

Reg Speller/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

Abracadabra! The origins of “hocus pocus”

The term “hoax” has its roots in the magician’s chant hocus pocus, explains Dave Wilton, editor of Wordorigins.org. “It’s almost certain that ‘Hocus Pocus’ was the stage name of a magician named William Vincent, who performed around the 1620s.”

Where Vincent derived the phrase remains uncertain. One popular theory suggests it’s a distorted version of the Latin phrase from the Catholic Mass, “Hoc est enim corpus meum,” meaning “This is my body.”

Though speculative, this theory fits the context of Vincent’s time. As an Englishman living during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), a period rife with religious conflict and anti-Catholic sentiment in Protestant England, such a linguistic twist would not be surprising.

Thomas Ady, a 17th-century critic of witchcraft, alludes to Vincent without naming him directly. Ady describes a man skilled in stage illusions during King James’s reign who called himself “The King’s Majesty’s most excellent Hocus Pocus,” uttering the phrase Hocus pocus, tontus talontus, vade celeriter jubeo-a cryptic mix of real Latin and gibberish meant to dazzle spectators.

For example, vade celeriter jubeo translates to “I command you to go quickly” in Latin, blending authentic language with playful nonsense reminiscent of a Harry Potter spell.

Wilton, however, remains skeptical of the religious origin, noting, “The Latin and liturgical connection doesn’t quite add up, so it’s difficult to see how ‘hocus pocus’ could have evolved directly from that.”

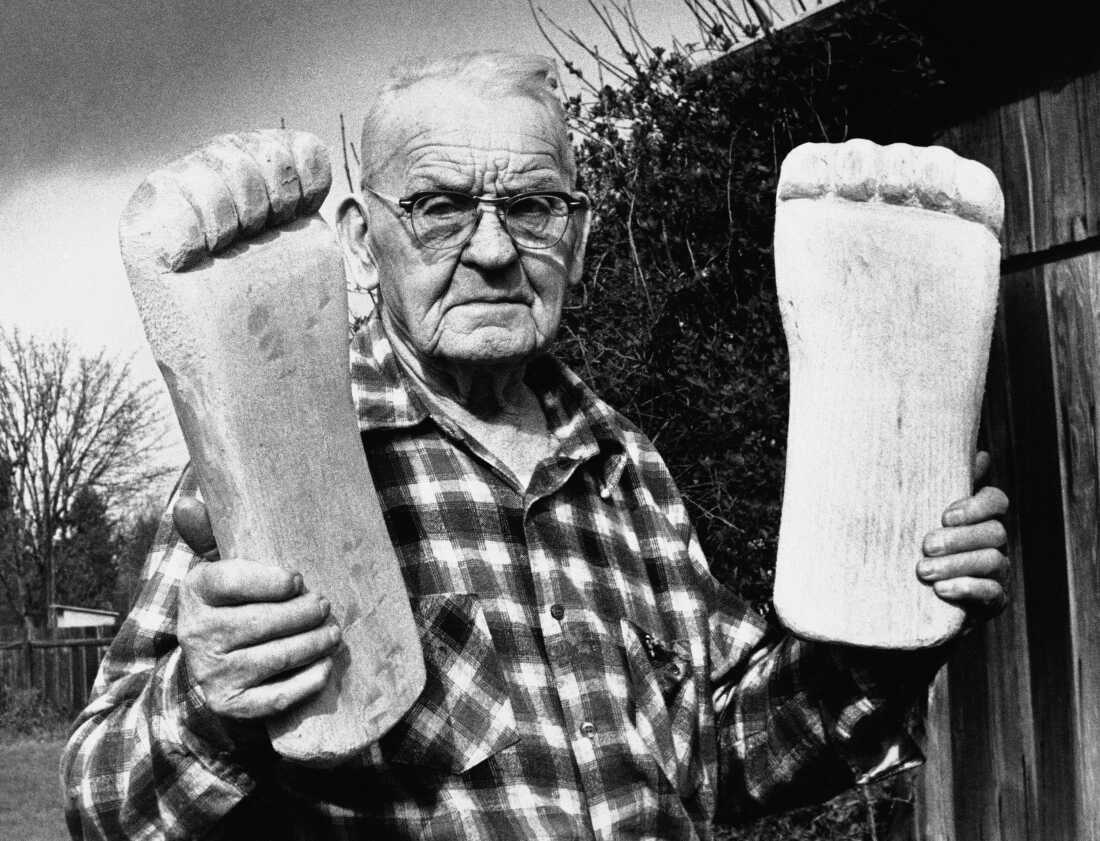

Rant Mullens showcases one of the many wooden feet he carved since 1928, which were used in Bigfoot hoaxes across the U.S. Northwest in 1982.

AP

hide caption

toggle caption

AP

Jim Steinmeyer, author of The Secret History of Magic: The True Story of the Deceptive Art, recalls hearing “hocus pocus” during his youth. “Magicians would invite the audience to say the magic words together,” he says.

“It’s a bit silly, but it works because it signals that something extraordinary is about to happen,” Steinmeyer adds.

How did “hocus pocus” evolve from a magician’s stage name-William Vincent was also a skilled juggler, according to Ady-to a term synonymous with magic itself?

Steinmeyer suggests it was an early form of branding. “Vincent repeated his stage name to the audience, making it part of the magical act’s formula.”

By seizing every chance to promote himself, Vincent ensured that “Hocus Pocus” became shorthand for the world of magic, even as the man behind the name faded into obscurity.

Vincent may also have penned one of the earliest magic manuals, Hocus Pocus Junior: The Anatomie of Legerdemain (1634). While the author remains officially anonymous, some scholars attribute it to him.

Tracing the evolution from “hocus pocus” to “hoax”

Transitioning from “hocus pocus” to “hoax” was a natural linguistic shift, Wilton explains. “Language is primarily spoken, so ‘hocus’ easily morphed into ‘hoax.'”

According to Merriam-Webster, the word “hoax” emerged as both a noun and a verb around the year 1800.

Konrad Kujau, infamous for fabricating Hitler’s diaries, displays copies of the forged documents during a civil trial in Hamburg, Germany, on August 29, 1984.

N. Foersterling/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

N. Foersterling/AP

While originally meaning a simple falsehood or trick, “hoax” today implies a more elaborate deception, notes Aja Raden, author of The Truth About Lies: A Taxonomy of Deceit, Hoaxes and Cons.

“It’s easier to persuade someone you own a private island than just a condo,” Raden explains.

Or even an entire nation, as history reveals.

In the 1820s, Gregor MacGregor claimed to have discovered Poyais, a fertile and thriving territory in Central America. “MacGregor launched an ambitious development plan but needed settlers and investors,” according to Historic UK. He attracted hopeful colonists from London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow, selling shares and raising an astonishing £200,000 in just one year. He even published a detailed guidebook, enticing adventurers with dreams of a new life in Poyais.

“The catch? Poyais was entirely fictitious,” Raden reveals. Hundreds of settlers embarked on voyages to this imaginary land, with some perishing and others arriving on a desolate stretch of Nicaragua’s Mosquito Coast.

The success of this grand deception lies in a common trait of hoaxes, Raden says: “Attempting to disprove a widely accepted falsehood often only strengthens belief. When I say, ‘Poyais isn’t real,’ all you hear is, ‘Poyais, go live there.'”

Jumping ahead a century, Raden points to an early example of “fake news.” In 1917, journalist H.L. Mencken fabricated a story claiming President Millard Fillmore installed the first bathtub in the White House.

This playful article quickly gained traction, being reprinted and accepted as fact. Mencken later confessed, “My motive was simply to have some harmless fun during wartime.”

However, The Museum of Hoaxes notes, “Mencken’s hoax was a deliberate test of readers’ and journalists’ gullibility, and it succeeded beyond his expectations.”

Decades later, President Harry S. Truman reportedly continued to proudly show visitors the White House bathtub, simply because, as Raden puts it, “he enjoyed believing the story.”