Jane Goodall, the renowned British primatologist and conservationist, revolutionized how we view the bond between humans and animals through her decades-long study of chimpanzees in their natural habitat.

Bertrand Guay/AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Bertrand Guay/AFP/Getty Images

Jane Goodall, whose pioneering work with wild chimpanzees earned her global recognition, has passed away at 91, as confirmed by the Jane Goodall Institute.

Her unique ability to bond with chimpanzees captivated the public, revealing through her research the striking similarities between these primates and humans.

“They kiss, hug, hold hands, and comfort each other. They express affection and empathy, but also display aggression and engage in primitive conflicts,” Goodall observed. “Because chimpanzees resemble us so closely, it prompts us to ask, ‘What truly distinguishes humans?'”

From a young age, Goodall aspired to live among animals and document their lives.

“My fascination began with Tarzan,” she shared in a 1990 interview with Terry Gross on WHYY’s Fresh Air. “I envied Tarzan’s Jane and thought she was too timid. I believed I would have been a far better companion for Tarzan – and honestly, I would have been.”

Born in London on April 3, 1934, Goodall’s early life was marked by her father’s departure to serve in World War II and her parents’ subsequent divorce. Raised in a sprawling Victorian home by her mother, sister, aunts, and grandmother in a coastal English town, financial constraints prevented her from attending university.

“My mother advised me to learn secretarial skills so I could find work anywhere if I decided to go abroad,” Goodall recalled. She completed secretarial training and, in 1956, after a friend invited her to visit a Kenyan farm, she worked as a waitress to save for a one-way ticket to Africa.

Upon arriving, she quickly sought out the paleontologist Louis Leakey.

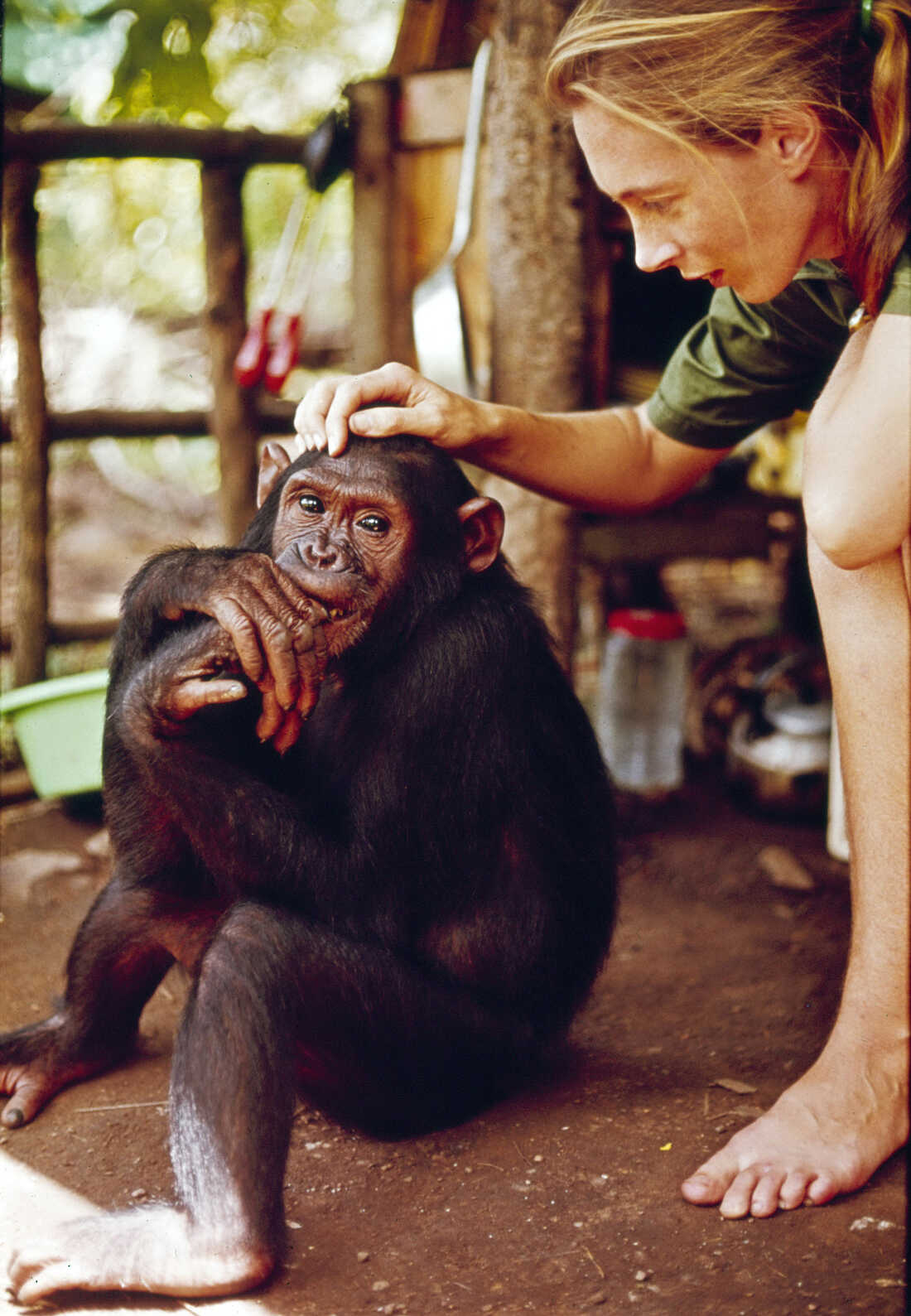

Jane Goodall interacting with a chimpanzee at Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, as seen in the 1965 television special “Miss Goodall and the World of Chimpanzees.”

CBS Photo Archive/CBS via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

CBS Photo Archive/CBS via Getty Images

According to Dale Peterson, Goodall’s biographer, Leakey was immediately struck by her vibrant passion and extensive knowledge about animals, despite her lack of formal education. He promptly hired her as his secretary.

While Leakey was focused on uncovering fossilized ancestors of humans, he believed that studying chimpanzees-the closest living relatives to humans-was equally vital. Goodall was his ideal candidate.

Leakey overlooked the fact that Goodall was a 26-year-old woman without a college degree, a rarity in the scientific community at the time. In 1960, he arranged for her to conduct research at what is now Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park.

“The authorities agreed but insisted she couldn’t live alone in the forest, deeming it inappropriate,” Peterson explained.

Consequently, Goodall brought her mother along as a chaperone. Both contracted malaria, and the chimpanzees initially fled from her presence. Undeterred, Goodall patiently offered bananas and approached the animals with quiet respect.

“Jane was the first to immerse herself with the chimpanzees, gradually earning their trust,” Peterson noted.

Within months, Goodall made a groundbreaking observation: chimpanzees could craft and utilize tools. She witnessed a chimp she named David Greybeard strip leaves from a twig to fish termites from a mound. Goodall fondly referred to him as her favorite chimpanzee.

She recounted to NPR how Leakey reacted: “He said, ‘It’s always been believed that only humans make tools. Now we must redefine what a tool is, what it means to be human, or accept chimpanzees as part of that category.'”

This revelation astonished the scientific world, as did Goodall herself. She affectionately named her subjects-David Greybeard, Fifi, Merlin, Flo-and described them as having distinct personalities and emotions.

Jane Goodall pictured in 1974 alongside her first husband, Hugo van Lawick, a wildlife photographer and filmmaker. They divorced the same year.

AP

hide caption

toggle caption

AP

Richard Wrangham, a biological anthropologist from Harvard who studied under Goodall, recalls that during the 1960s, animals were often viewed as mere automatons.

“Goodall’s empathy for animals was extraordinary,” Wrangham said. “But what stands out most is her unwavering honesty in reporting her observations.”

She boldly acknowledged that chimpanzees possess minds and emotions, and she did not shy away from revealing their darker behaviors, including violent attacks, killings, and even cannibalism.

On WHYY’s Fresh Air, Goodall described witnessing what resembled warfare among chimps. “It was heartbreaking and shocking,” she said. “But it made them even more like us than I had imagined.”

By 1965, Goodall graced the cover of National Geographic, and her work was featured in numerous books and documentaries, cementing her status as a real-life counterpart to Tarzan’s Jane.

Over time, she reduced her fieldwork, delegating research to students and colleagues. She had a son with her first husband, a photographer, and later married a politician. In 1977, she established The Jane Goodall Institute to advocate for chimpanzee conservation and environmental protection.

Her perspective shifted profoundly in 1986 at a chimpanzee researchers’ conference in Chicago, where she learned about the threats chimps faced from poaching, habitat loss, and medical testing.

“I realized I could no longer live in my own bubble,” she reflected. “I had to use my knowledge to make a difference.”

Jane Goodall shares a playful moment with Bahati, a 3-year-old female chimpanzee at the Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary near Nanyuki, Kenya, in 1997.

Jean-Marc Bouju/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Jean-Marc Bouju/AP

From then on, Goodall became a tireless advocate, traveling extensively to raise awareness while returning to her childhood home between engagements. Despite the demanding schedule, she found solace in the global community of friends she cultivated.

When asked whether she preferred chimpanzees or humans, she often replied, “It depends.”

“Chimpanzees are so similar to us that I like some people more than some chimps, and some chimps more than some people,” Goodall remarked.

Jane Goodall delivering a speech during the United Nations 2014 Equator Prize Gala at Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center, New York City.

D Dipasupil/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

D Dipasupil/Getty Images