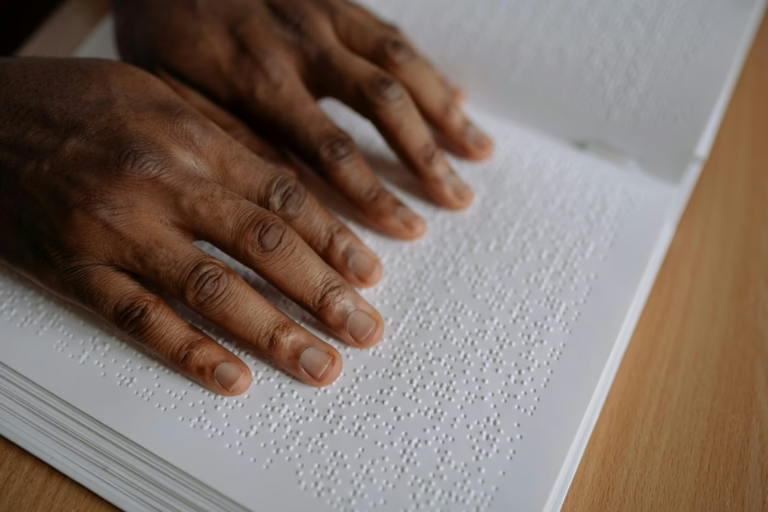

In June 2023, United Bank for Africa (UBA) garnered attention as the pioneering Nigerian financial institution to unveil a braille-enabled account opening form. This initiative was hailed as a significant advancement in promoting financial accessibility, with acclaimed musician Cobhams Asuquo praising it as a breakthrough addressing “the challenge of access, which has long hindered individuals like me who are visually impaired.”

However, two years on, numerous blind customers of UBA report that the reality of the account opening experience does not align with the bank’s initial commitments. Conversations with over a dozen visually impaired clients from various Nigerian states reveal that most have neither encountered nor been informed about the braille forms. Those who did noted that such forms were not made available at their local branches. Many recounted ongoing discriminatory behaviors, including demands to bring sighted helpers to complete paperwork, refusal to issue ATM cards, and being compelled to sign legal documents not required of sighted patrons.

A celebrated debut, yet limited accessibility

The braille form was officially launched at a well-publicized event held at UBA’s Lagos headquarters on June 27, 2023. The ceremony included senior bank officials, representatives from Lagos State’s disability agencies, and Cobhams Asuquo, who endorsed the form as transformative for blind Nigerians. UBA declared that this tool would “enable visually impaired customers to independently initiate and finalize the account opening process.”

Despite these promises, the on-the-ground reality tells a different story.

Eja Eji, who opened an account in Nsukka in early 2024, shared that he was unaware of the braille form and was never offered one during his visit. “Had I not brought it up, I wouldn’t have known such a form existed,” Eji told TechCabal. Instead, bank personnel insisted he bring a sighted individual to assist with the process.

Such experiences are widespread. In Nigeria, opening certain bank accounts typically requires physical attendance at a branch to complete paperwork, collect ATM cards, or activate mobile banking services. While many banks allow initial online steps, the process cannot be fully completed remotely. For blind customers, this presents unique obstacles, as most forms are only available in print and staff often lack training to provide accessible alternatives. Several visually impaired interviewees revealed they have ceased visiting bank branches due to repeated negative encounters, including being told they cannot use thumbprints or being forced to bring a guarantor before their accounts could be opened.

Olapade Olorunwa, a UBA customer for three years, recalled her difficult first attempt to open an account in 2022. “It was so frustrating that I couldn’t complete the process until I brought a sighted friend,” she said. When she opened another account in August 2023, shortly after the braille form’s introduction, she noted, “No one mentioned the braille form to me.”

Similarly, Olayinka Samson, a 23-year-old University of Ilorin student, reported a smooth initial account setup in 2022 but said the braille form was never referenced during later visits.

Challenges extend beyond account setup

For many blind clients, difficulties are not confined to opening accounts. Numerous individuals described systemic barriers when accessing basic banking services such as managing accounts, obtaining or using debit cards, making withdrawals or transfers, and setting up mobile applications. Rather than being straightforward, these services are often denied or come with additional conditions not imposed on sighted customers.

Joseph Afolabi, a disability rights advocate and UBA client, recounted his experience at the Abule Egba branch in May 2025 when he was required to sign a court indemnity form before receiving an ATM card.

Indemnity forms serve to protect banks from liability in case of disputes or losses related to account or card usage, typically requested when banks perceive elevated risk.

Afolabi explained the urgency of obtaining the card as he was managing funds as treasurer for a secondary school alumni project. Without the card, he could not delegate account access to team members. “The delay almost disrupted our project. I eventually signed the form because I was about to leave Lagos and lacked mobile banking access due to the ATM card issue,” he said.

Such accounts highlight how inaccessible banking procedures not only frustrate blind customers but also threaten their community and professional responsibilities. In some instances, these barriers have caused direct financial harm to those relying on banking services for their livelihoods.

Cherish Nnenna, who operated a POS business at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka in 2024, shared that UBA’s refusal to issue her an ATM card negatively impacted her enterprise.

Without a card, she had to visit the bank physically each time she needed cash to serve customers. “There were weekends I earned nothing because the bank was closed, and I had no funds left. I had to borrow money until I could access the bank again,” she explained. This experience led her to switch to fintech alternatives. “It was a difficult period until I started using Opay. With Opay, I could easily transfer money or use my Fidelity account to receive payments.”

For many, being denied ATM cards meant more than lost income; it undermined their autonomy. Relying on family or bank staff for routine transactions eroded their dignity and reinforced damaging stereotypes that blind individuals cannot manage their finances independently.

Okpala Chidebere, who banked at UBA branches in Nsukka and Nnewi, recalled being told she must open a joint account with her sister to receive an ATM card. “If I came alone, staff would reprimand me for not bringing a guide,” she said. “First Bank has similar policies, but not as stringent as UBA’s.”

Oluchi Ekeh, who opened her account at UBA Nsukka in 2022, was bluntly informed she could not have an ATM card due to her blindness. “That day was very disheartening,” she said. She now maintains a savings-only account and described being turned away by security personnel who insisted she bring someone with her. “If I come alone, they refuse to assist me.”

Even when staff were courteous, the outcome often remained exclusionary: blind customers were denied full access to banking tools, illustrating how discrimination can be systemic without overt hostility. A customer in Abeokuta noted that while her branch politely refused ATM cards to blind clients, another branch in the same city issued cards readily if accompanied by a helper.

UBA did not respond to detailed inquiries about the braille form’s implementation or the treatment of visually impaired customers across its branches.

An opportunity overlooked

At the braille form’s launch, UBA’s executive director for finance and risk management, Ugo Nwaghodoh, emphasized the aim “to guarantee everyone the right to select the type of account they wish to operate.”

Yet, the experiences shared by blind customers raise doubts about the form’s availability and the bank’s genuine commitment to financial inclusion, especially given the persistent obstacles faced during account opening and product access.

“Frankly, the UBA braille form perpetuates the financial exclusion experienced by blind Nigerians,” said Gbenga Ogundare, a Lagos-based blind journalist. “It does not truly ensure accessibility because it still requires sighted assistance. It feels more like public relations than a real innovation.”

Beyond limited distribution, concerns have emerged about whether bank staff receive adequate disability inclusion training.

“Do UBA employees even understand braille? Are they equipped to assist blind customers?” questioned Olamide Daniel, a disability consultant and UBA business client. “The braille form doesn’t deliver the independence the bank claims. Did they provide tools to complete the form, or are customers expected only to read it? Sighted customers use pens to fill forms-what accommodations exist for blind users? The bank should address issues like indemnity forms and thumbprint refusals before promoting independence.”

These challenges reflect broader shortcomings in Nigeria’s banking sector, where accessibility initiatives often fail to translate into practical improvements for the country’s over 7 million visually impaired individuals, many of whom bank with UBA.

Similar discriminatory practices are reported at other major banks. At Union Bank’s Ogbomoso branch in Oyo State, Abiodun Jephta was outright denied an ATM card. “They told me I couldn’t have one because I’m blind. Despite my explanations, they refused,” he said. Unlike UBA, he was not even offered an indemnity form option.

Olorunwa faced comparable rejections at two First Bank branches. In 2024, staff at the Lawansin Surulere branch demanded she sign an indemnity form in court, while the University of Ilorin branch refused to issue her a card. “I currently don’t have an ATM card because I see no reason to sign such a form,” she stated.

Discrimination extends beyond card issuance. Michael Chukwudi, who opened a Zenith Bank account online, was told at the Onitsha electronic market branch that they could not assist with account updates because he was blind and unable to sign, and the branch lacked thumbprint identification. He eventually abandoned the account.

Blessing Harrison experienced restrictive treatment at a First Bank branch in Ebonyi, where she was told she shouldn’t have an ATM card and needed a signatory. When she requested to use withdrawal slips instead, staff refused until she threatened to close her account.

First Bank and Union Bank did not respond to requests for comment by the deadline.

Hostility sometimes arises from unexpected quarters. David Eche recounted being humiliated by a Guaranty Trust Bank security guard in Makurdi who questioned why he had been issued an ATM card. “The guard loudly questioned the decision and shouted at me. Since then, I stopped banking with GT,” he said.

A bank official, speaking anonymously, acknowledged progress over the past three years in financial inclusion efforts. The official noted that text-to-speech software has been enabled on some ATMs and that the bank is working to introduce braille forms and enhance digital accessibility. Additionally, a link has been published on the bank’s website to help customers locate accessible ATMs.

These initiatives align with the Central Bank of Nigeria’s 2020 Guidelines on Operations of Electronic Payment Channels, which require at least 2% of ATMs to feature tactile symbols for visually impaired users. The guidelines also mandate that banks publicly disclose the locations of such ATMs on their websites.

Despite the policy’s five-year tenure, few ATMs currently meet these standards. Banks failing to comply face penalties, including suspension from deploying new ATMs and fines of ₦1 million per non-compliant machine.

Regarding indemnity forms, the official described them as necessary tools balancing efficient service delivery with risk management. They enable prompt processing of requests from visually impaired customers, such as document replacements or transactions, while clarifying responsibilities.

Addressing customer complaints about negative branch experiences, the official stated:

“We uphold the highest standards in serving all clients, including those who are blind or visually impaired. Our commitment is to ensure their banking experience is safe, inclusive, and respectful at every interaction.

We acknowledge past concerns and view them as opportunities to better understand and meet unique needs. Feedback is taken seriously to drive improvements. Our objective is simple: every customer, regardless of ability, should feel valued, supported, and confident banking with us.”

Legal safeguards and enforcement gaps

Visually impaired customers are protected under Nigeria’s Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018, which explicitly prohibits unfair treatment based on disability. Section 1 states: “A person with disability shall not be discriminated against on the ground of his disability by any person or institution in any manner or circumstance.” Yet, the lived experiences of blind customers indicate that enforcement remains inadequate, leaving millions marginalized in accessing financial services.

Additional Central Bank of Nigeria frameworks-including the Consumer Protection Framework 2016, the National Financial Inclusion Strategy 2022, and the Nigerian Sustainable Banking Principles-mandate fair treatment, equal access, and tailored products and guidance for persons with disabilities.

While these policies exist, the challenge lies in their practical implementation. Until banks prioritize the needs of persons with disabilities and actively involve them in policy development, initiatives like UBA’s braille form or the contentious indemnity form risk being perceived as superficial gestures rather than genuine strides toward inclusion.

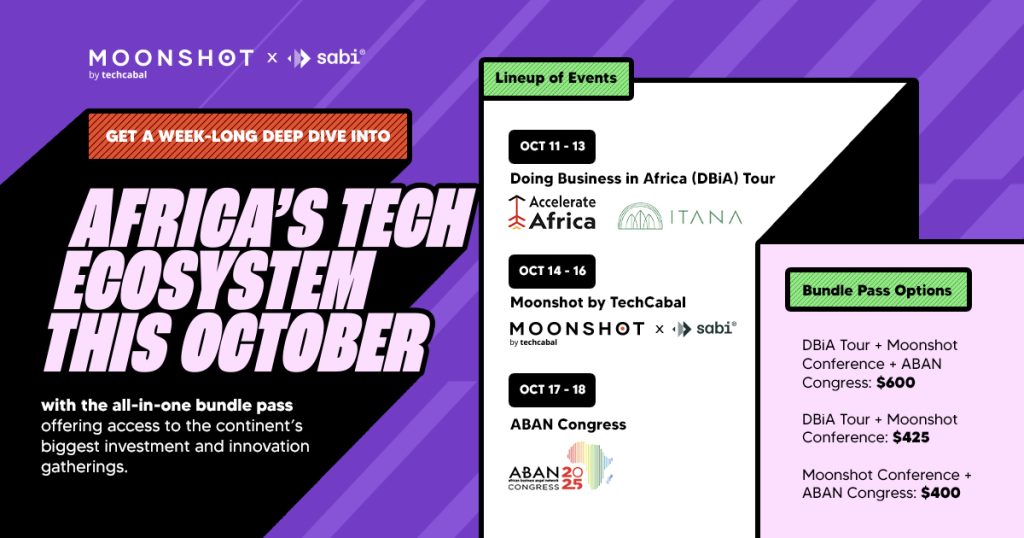

Save the date! Moonshot by TechCabal returns to Lagos on October 15-16! Join Africa’s leading founders, creatives, and tech innovators for two days of inspiring keynotes, networking, and forward-thinking ideas. Secure your tickets now at: moonshot.techcabal.com

0 Comments