Four-year-old Caleb Strickland relies on an artificial heart pump to survive while awaiting a transplant. His mother, Nora Strickland, shares how distant the political conflicts involving the Trump administration and universities feel from their daily reality.

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

About the size of a AA battery, this innovative device offers hope by sustaining the heartbeat of infants and babies facing heart failure.

Known as the PediaFlow, this implantable artificial heart pump is designed specifically for the most fragile pediatric patients. James Antaki, a biomedical engineer at Cornell University, has dedicated over twenty years to perfecting this life-saving technology.

By spring of last year, the PediaFlow was nearing the completion of its research and production phases, poised for clinical trials thanks to a $6 million multi-year grant from the Department of Defense.

“The possibilities here are immense,” Antaki remarks, often carrying a prototype of the device in his pocket as a symbol of hope. “We’re on the brink of deploying a technology that could save countless children’s lives.”

In the United States, congenital heart defects affect approximately 1 in every 100 newborns. Yet, for the youngest patients with severe heart conditions, no artificial heart device has been tailored to their unique needs. The FDA has recognized this gap as a critical shortage in medical device availability.

The PediaFlow prototype, a compact heart-assist device designed for pediatric patients.

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

However, in April, the Trump administration terminated Antaki’s federal funding as part of a broader crackdown on prestigious universities accused of civil rights violations and inadequate responses to antisemitism on campuses. This move resulted in the cancellation of approximately $10 billion in grants, including nearly $250 million allocated to Cornell University.

“We feel like unintended victims,” Antaki says, unable to comprehend how his medical research could be linked to political disputes over campus culture. “Our mission is to contribute positively to society, not to be caught in political crossfire.”

James Antaki, biomedical engineering professor at Cornell University, pictured in his research lab.

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

Meanwhile, families far removed from political debates and academic institutions bear the consequences of these funding decisions.

A Young Child Battling Heart Failure

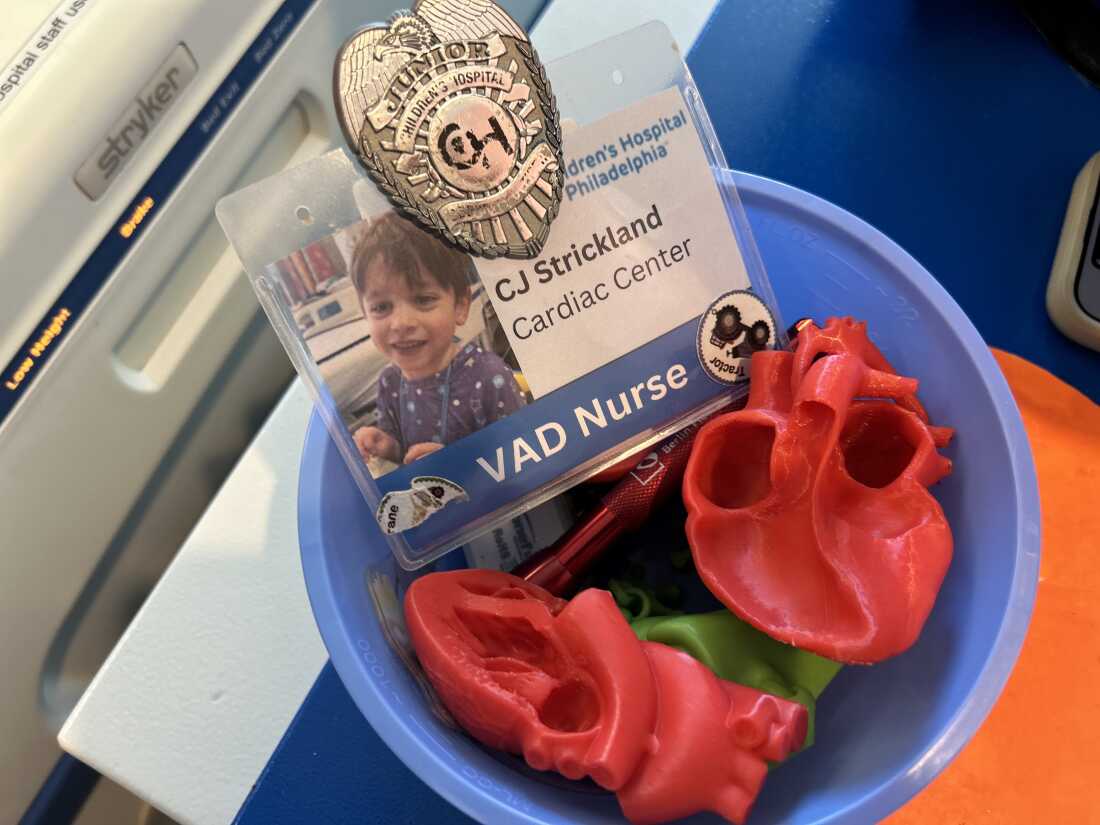

Inside a room on the sixth floor of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Nora Strickland offers her son Caleb a blue popsicle, which quickly colors his lips, tongue, and teeth a vivid cobalt hue.

At four years old, Caleb has developed heart failure after a viral infection severely damaged his already fragile heart. Since May, he and his family have been living in the hospital, where an external ventricular assist device (VAD) sustains his heartbeat as he awaits a transplant that could take up to a year.

“Mom, what does VAD mean?” Caleb asks.

Nora explains that because Caleb was born with a congenital heart defect and has only one functioning ventricle, he requires a ventricular assist device to help his heart pump blood.

In the U.S., most infants and toddlers with heart failure who need a VAD rely on external devices due to limited space in their chest cavity.

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

The current device Caleb uses is roughly the size of a hockey puck, filled with blood, and hangs from his slender frame.

Most young children in heart failure in the U.S. depend on the Berlin Heart, an external ventricular assist device, since their small chest cavities cannot accommodate an implant. This device’s power source is bulky, weighing over 100 pounds, mounted on wheels, and can only be disconnected for brief periods.

After lunch, Caleb heads to the hospital’s playroom for art activities, a process that requires careful coordination due to the equipment he must bring along.

“I’m going to unplug Taco,” Nora says, referring to the power source, “and you’ll have to push Broccoli,” the nickname for the pole carrying his blood-thinning medications.

Caleb has affectionately named his medical devices: the power supply is “Taco Bell,” the medication pole is “Broccoli,” and his heart pump is “Henry,” after his favorite Thomas the Tank Engine character. These devices are his constant companions.

Artwork created by children decorates Caleb’s hospital room at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

A plastic heart model and a play name tag are visible in Caleb’s hospital room.

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

“We have to take all these with us because, look,” Caleb says, lifting his shirt. “They’re connected to me. This is my VAD, and it helps my heart. Let’s go!”

They have just 20 minutes to reach the playroom and reconnect to the wall power before an alarm sounds.

“It could be worse, Mom!” Caleb jokes.

“It could always be worse, sweetheart,” Nora replies.

Yet, Nora confides that things could also improve.

If Caleb had access to a portable implant like the PediaFlow, “he could play outside, be at home, and move freely without being tethered to a wall,” she says.

Caleb affectionately names his medical equipment: the large power supply is “Taco Bell,” the medication pole is “Broccoli,” and his heart pump is “Henry.”

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Elissa Nadworny/NPR

This hospital environment feels worlds apart from the political battles involving the Trump administration and academic institutions, yet Nora’s family is directly impacted by decisions beyond their control.

She questions why research with the potential to aid families like hers would be abruptly halted.

When the Department of Defense informed Antaki in April about the stop-work order, the message cited “direction from the Administration” without further explanation. Subsequent inquiries received similar vague responses.

Following the FDA’s recent designation of pediatric ventricular devices as critically scarce, inquiries to the Department of Health and Human Services about the grant cancellation yielded no specific comments, only assurances that public access to safe and effective medical devices remains a priority.

The Future of Pediatric Heart Device Innovation

For pediatric cardiologists treating children with heart failure, advancements in device technology are urgently needed.

“This area demands our focus, resources, and collaborative effort,” says Jonathan Edelson, pediatric cardiologist and medical director of the Heart Function, Transplant, and VAD Program at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “We recognize the urgent need for smaller, more compatible devices for these tiny patients.”

Despite its limitations, the VAD Caleb uses performs effectively for children, though it remains external and reliant on a cumbersome power source.

“Children cannot return home with this device, which is even more challenging than the mobility restrictions,” Edelson explains. “I hope this is a temporary solution.”

A whiteboard in Antaki’s Cornell lab displays schematic diagrams. He expresses frustration over the funding cuts.

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

Edelson remains hopeful about ongoing innovations. His hospital participates in a clinical trial testing a smaller, more portable power driver for VADs with extended battery life, though Caleb was ineligible for this study.

“The progress in this field is tangible,” he says. “With technological advances, enhanced collaboration, and refined patient selection, the outlook for children with heart failure needing VADs has never been more promising.”

Still, from a parent’s viewpoint, “you want these devices to evolve rapidly – fully implantable pumps without external batteries or power sources, enabling children to live as normal a life as possible.”

Since the funding halt, Antaki has been inundated with messages from families eagerly awaiting the PediaFlow and from parents whose children might have benefited from it previously.

One such message came from Ned Place, a fellow Cornell professor.

Ned Place lost his daughter Ingrid shortly after birth due to hypoplastic left heart syndrome, a condition the PediaFlow aims to address.

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

Place’s daughter, Ingrid, passed away just one day after birth from hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the same congenital defect affecting Caleb.

“Her heart failed within hours of birth,” Place recalls, his voice heavy with emotion, reflecting on the terrifying moments over three decades ago.

“The PediaFlow could have extended Ingrid’s life, giving our family precious time. While it’s too late for her, I think about the families who might benefit in the future.”

Ned Place wears a bracelet engraved with the names of his three children, including Ingrid. He marks her birthday on the calendar every year.

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Heather Ainsworth/for NPR

For now, the future of this vital technology remains uncertain.

“I’m growing increasingly discouraged,” Antaki admits. “Unless this funding is reinstated, I don’t see a way forward.”

He holds out hope that Cornell might negotiate with the administration to restore the grant, as some other top universities have managed.

Yet, the reality is stark: his lab has been inactive for over six months, graduate students have departed, his lead technician was laid off, and alternative funding remains elusive.