On September 22, 2025, Katsina State hosted a pivotal one-day forum aimed at reforming the Almajiri and Islamiyya education systems, marking a significant stride toward addressing a persistent national challenge. Spearheaded by Governor Dikko Umaru Radda, the gathering united religious authorities, parents, government representatives, development partners, and key stakeholders to critically assess the system’s shortcomings and craft tailored solutions. Confronted with high rates of school absenteeism, widespread poverty, and security concerns, Katsina underscored the urgency of conducting a comprehensive Almajiri census to enable data-driven planning, foster inclusive program development, and drive legislative reforms.

This initiative builds upon earlier local discussions held in July 2025 and broadens the scope to evaluate the overall progress of Almajiri education reforms across Northern Nigeria. It calls for a thorough examination of federal efforts, including those led by the National Commission for Almajiri and Out-of-School Children Education (NCAOOSCE), through a detailed Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis to extract valuable lessons and chart future directions. With Nigeria facing a staggering figure of over 18 million out-of-school children-predominantly in the northern regions-Katsina’s approach offers a replicable model for nationwide implementation.

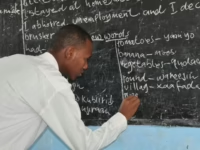

Reform efforts in Northern Nigeria’s Almajiri system have progressed gradually but remain challenged by numerous obstacles. Since the enactment of the Universal Basic Education Act in 2004, which mandated the integration of traditional Quranic schools into the formal education framework, various states have piloted hybrid models combining religious teachings with secular subjects. In 2025, NCAOOSCE intensified its initiatives by enrolling thousands of children into mainstream education and collaborating with states like Yobe, which allocated N750 million toward Almajiri infrastructure development. Kano’s July 2025 revitalization program successfully enrolled 5,000 students in blended schools, while Bauchi introduced vocational training within its model schools. Federal schemes such as the Better Education Service Delivery for All (BESDA) have impacted over 1.5 million children since 2018, contributing to a decline in street begging in targeted areas. Nevertheless, enrollment rates remain modest, with UNESCO estimating only slight reductions within the 10 million-strong Almajiri population.

Evaluations of federal programs reveal a mixed picture. Since its establishment in 2019 and restructuring in 2022, NCAOOSCE has constructed more than 100 model schools nationwide and integrated 18,670 teachers into the formal system by mid-2025. However, reports from the International Rescue Committee and ResearchGate highlight persistent enrollment challenges, largely due to resistance from Mallams who perceive reforms as threats to Islamic traditions. In regions like Sokoto and Kano, entrenched cultural preferences for religious education over secular learning have hindered progress, compounded by poverty that compels parents to send children away as a form of social security. Despite a 2025 budget allocation of N1.5 billion, including funding for certification programs at institutions such as Federal University Dutsinma, implementation gaps-such as underutilized funds and poor coordination-have limited the reforms’ reach. An Anti-Slavery International report from 2025 warns that without tackling the links to child labor, these reforms risk perpetuating exploitation.

A SWOT analysis reveals the multifaceted nature of the Almajiri system. Its strengths lie in deep cultural roots and the potential to impart moral values, as acknowledged by Katsina stakeholders who emphasize its role in character development. Conversely, weaknesses include the system’s susceptibility to child begging, health hazards, and a lack of formal skills training, which the Northern Elders Forum describes as a “ticking time bomb” for regional security. Opportunities exist in integrating formal certification programs like Dutsinma’s, which enhance employability, and BESDA’s vocational components. However, threats such as conflict-induced displacement in Borno, climate-related disasters like floods in Adamawa, and inconsistent policy implementation-often due to funding shortages and poor planning-pose significant risks to sustainable reform.

Comparing Katsina’s proactive measures with the crisis in Borno highlights stark regional disparities. Katsina’s culturally informed strategy identifies key failure factors, including rapid social changes and large family sizes, and proposes establishing a state commission alongside unified legislation for Tsangaya schools. This approach aims to reduce the estimated 1.5 million out-of-school children in the state. In contrast, Borno faces compounded challenges from insurgency and devastating floods in September 2025, which displaced two million children, destroyed temporary learning centers, and worsened conditions for 2.2 million internally displaced persons in the Northeast. Yobe’s N750 million budget allocation, while significant, falls short amid escalating security threats, stalling reform efforts. Public discourse on social media reflects widespread frustration, with many questioning why successful models like Kano’s are not expanded to conflict-affected areas.

Insights from Katsina and national reform initiatives offer valuable guidance. Inclusive stakeholder engagement fosters ownership and mitigates resistance often caused by top-down approaches. Federal programs must enhance coordination, as demonstrated by NCAOOSCE’s achievements in teacher integration when adequately funded. The SWOT framework suggests capitalizing on cultural strengths through hybrid curricula while addressing vulnerabilities via safe school initiatives. Moving forward, replicating Katsina’s census model nationwide for evidence-based planning, allocating at least 15 percent of state budgets to education, and partnering with NGOs to expand vocational training are critical steps. Additionally, the federal government should enforce the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) mandate on integration and implement poverty alleviation measures, such as conditional cash transfers, to discourage child migration.

Katsina’s recent engagement offers a beacon of hope, yet without decisive national action, the Almajiri divide risks deepening. By adopting these lessons, Nigeria can transform this cultural institution into a robust educational asset.