Kishanganj/Katihar, India – Over ten years ago, Mukhtar Alam* attended a government school in Kishanganj, the only district in Bihar with a Muslim majority in eastern India. During that time, he shared a close friendship with several Hindu classmates.

Alam and one Hindu friend, in particular, were inseparable, collaborating on schoolwork and projects. To respect his friend’s vegetarian lifestyle, Alam would refrain from eating meat when they shared meals.

However, a divisive event two years ago shattered their bond, and reconciliation has yet to occur.

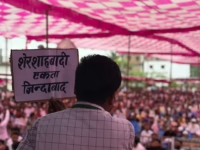

At a political rally in Kishanganj, Jitanram Manjhi, a former Bihar chief minister and a key ally of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), labeled the Shershahbadi Muslim community as “infiltrators” from Bangladesh, India’s eastern neighbor, where over 91 percent of the population is Muslim and primarily speaks Bangla.

The name “Shershahbadi” traces back to the historic Shershahbad region, which spans parts of West Bengal. This term itself is linked to Sher Shah Suri, an Afghan ruler who defeated the Mughals and briefly governed areas now known as Bihar and Bengal (including Bangladesh) in the 16th century.

Distinct from the Hindi dialects and Urdu commonly spoken in Bihar, the Shershahbadi Muslims communicate in a Bangla dialect infused with Urdu and Hindi vocabulary. Locally, they are often called “Badia” or “Bhatia,” terms derived from “Bhato,” meaning moving against the river’s current. This reflects their migration upstream along the Ganges-from Malda to Murshidabad in West Bengal, and eventually to Bihar’s Seemanchal region, one of India’s poorest areas.

“Manjhi’s remarks felt threatening,” Alam, a business administration graduate and member of the Shershahbadi community, shared with Al Jazeera.

Determined to respond, he posted a rebuttal on Facebook. Moments later, a Hindi comment appeared beneath his post: “You people are Bangladeshi infiltrators.”

Shockingly, the comment came from his closest friend.

“Seeing that message sent chills through me,” said the 30-year-old, seated beneath the thatched roof of a primary school he manages. “It fractured our trust and ended our brotherhood.”

Alam represents one of approximately 1.3 million Shershahbadi Muslims in Bihar, according to a 2023 state “caste census,” with the majority residing in Kishanganj and Katihar districts.

As Bihar, India’s third most populous state, approaches pivotal legislative elections that could influence national politics, these districts have become focal points of an intense BJP campaign targeting alleged “Bangladeshi infiltrators.”

The Targeting of Shershahbadi Muslims

On India’s Independence Day last month, Prime Minister Modi addressed the nation from the historic Red Fort in New Delhi, announcing the creation of a “high-powered demography mission” aimed at identifying infiltrators.

“No nation surrenders itself to infiltrators. No country in the world does-so why should India?” Modi declared, without naming specific groups. He promised the mission would tackle the “serious crisis” facing the country in a “deliberate and timely” fashion, though details remain undisclosed.

Right-wing Hindu factions frequently brand Bangla-speaking Muslims in Bihar, West Bengal, and Assam as “Bangladeshi infiltrators.” In Assam, where the BJP has governed since 2016, the state administration has actively campaigned against Bangla-speaking Muslims, labeling them “outsiders” and accusing them of demographic manipulation.

Muslims constitute nearly one-third of Assam’s population-the highest proportion among Indian states-surpassed only by Indian-administered Kashmir and the Lakshadweep islands.

In Bihar, Muslims number around 17 million, about 17 percent of the state’s 104 million residents, per the 2011 census. Nearly 28.3 percent of these Muslims live in Seemanchal (“frontier region” in Hindi), which includes Kishanganj, Katihar, Araria, and Purnia districts. Katihar, Kishanganj, and Purnia border West Bengal, while Bangladesh lies just a few kilometers from Seemanchal.

Bihar’s state assembly elections are scheduled in two phases on November 6 and 11, with results announced on November 14.

The BJP has never governed Bihar independently, often relying on coalitions with regional parties over the past two decades. Critics accuse the party of exploiting the “Bangladeshi infiltrator” narrative in Seemanchal to sow religious and linguistic divisions among voters.

Alam notes that his concerns have intensified in the past two years as Modi himself spearheads the BJP’s campaign against his community.

“Politicians playing vote bank politics have branded Purnia and Seemanchal as infiltration hotspots, jeopardizing the region’s security,” Modi stated during last year’s general election campaign in Purnia.

He reiterated this stance at multiple BJP rallies across Bihar this year.

“A massive demographic crisis has unfolded in Seemanchal and eastern India due to infiltrators,” Modi declared in Purnia last week, vowing to “expel every infiltrator.”

This crackdown is already underway in other Indian states.

“Demons Have Arrived from Bangladesh”

BJP-led state governments have intensified efforts to deport alleged “illegal” Bangladeshi nationals, with hundreds of Bengali-speaking individuals expelled from Assam, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and New Delhi-despite many possessing valid Indian citizenship documents. Critics argue these actions disproportionately target Muslims.

Recently, Assam’s BJP unit released an AI-generated video titled “Assam Without BJP,” warning that Muslims would soon constitute 90 percent of the population, dominating public spaces such as tea gardens, airports, and stadiums, permitting “illegal” Muslim migrants through barbed wire fences, and legalizing beef consumption-a contentious issue since many upper-caste Hindus abstain from beef, and its sale is banned in most Indian states.

For Seemanchal’s Muslims, the “Bangladeshi infiltrator” label is a familiar and painful refrain, fueled by the community’s dense presence and proximity to Bangladesh.

Locals say the BJP has long sought to transform Seemanchal into a “Hindutva laboratory,” a term linked to Modi’s home state of Gujarat, where he became chief minister in 2001. Hindutva, meaning “Hinduness,” describes the BJP’s Hindu nationalist ideology. Shortly after Modi’s rise in Gujarat, nearly 2,000 Muslims were killed in one of modern India’s worst communal massacres.

“Whenever a Hindu majoritarian leader visits Seemanchal, we brace ourselves for hostile remarks and their consequences,” Alam told Al Jazeera.

Last month, Giriraj Singh, federal Minister of Textiles and a Bihar-based BJP leader, declared at a Purnia rally: “Many demons have come from Bangladesh; we must eliminate those demons.”

In October 2024, Singh organized a “Hindu Pride March” in Seemanchal and neighboring Bhagalpur, both with significant Muslim populations. During the event, he repeatedly invoked Bangladeshi infiltration and other divisive issues targeting Muslims, including Rohingya refugees and the “love jihad” conspiracy theory, which alleges Muslim men seduce Hindu women to convert them to Islam.

“If these Badias [Shershahbadis], infiltrators, and Muslims strike us once, we will retaliate a thousand times,” Singh proclaimed to an enthusiastic crowd in Kishanganj last year.

BJP legislator Haribhushan Thakur defended the party’s campaign against Shershahbadi Muslims in Bihar, telling Al Jazeera, “This is not about polarization or elections. The Muslim population is increasing in Seemanchal due to infiltration, so action is necessary. If unchecked, Seemanchal could become Bangladesh within 20-25 years.”

Pushpendra, a former social work professor at Mumbai’s Tata Institute of Social Sciences, expressed skepticism about the BJP’s strategy in Seemanchal.

“The BJP raised the infiltrator issue in the 2024 Jharkhand assembly elections, but it failed because the allegations lacked evidence,” he said, referring to the tribal-majority state neighboring Bihar.

“The same will happen in Bihar since there is no Bangladeshi infiltration in Seemanchal. Besides, Seemanchal doesn’t even share a border with Bangladesh.”

A Longstanding Campaign

The campaign against Bangla-speaking Muslims, branding them as Bangladeshi infiltrators, originated in Assam during the late 1970s when a student group demanded their expulsion. Thousands of Muslims were either deported or declared “doubtful” citizens, leaving their legal status in limbo and exposing them to persecution.

This movement soon spread to Bihar, where the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the student wing of the far-right Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), first raised the issue. Founded in 1925, the RSS, which ideologically guides the BJP, has at times drawn inspiration from European fascist movements and aims to transform secular India into a Hindu ethnic state. The organization operates thousands of chapters nationwide and counts Modi and other BJP leaders among its lifelong members.

In the early 1980s, the ABVP alleged that 20,000 Bangladeshis had been added to voter lists in Seemanchal. They demanded a review similar to Assam’s, where millions of Bengali-speaking Muslims with Bangladeshi ancestry reside.

The Election Commission of India complied in 1983, issuing notices to nearly 6,000 Muslims-exclusively from the Shershahbadi community-to prove their citizenship.

“They were asked to present land ownership documents. We organized camps, gathered documents, and took a delegation to Patna,” recalled Jahangir Alam, now in his seventies, who fought the ABVP’s campaign by submitting proof of citizenship. The effort succeeded, and no citizenships were revoked.

“The entire episode was orchestrated by the ABVP,” Jahangir told Al Jazeera.

Today, the campaign has resurfaced in Seemanchal, with BJP leaders demanding a National Register of Citizens (NRC) similar to Assam’s. The NRC is a registry intended to identify and exclude undocumented migrants.

Assam completed its NRC in 2019, excluding nearly two million people as non-citizens. Modi’s government has expressed intentions to implement the NRC nationwide.

“The demographics of Katihar, Kishanganj, Araria, Purnia, and Bhagalpur have shifted due to Bangladeshi infiltrators,” BJP parliamentarian Nishikant Dubey asserted in parliament in 2023.

“I urge the government to enforce the NRC to expel all Bangladeshis.”

Akbar Imam*, a farmer from Katihar’s Shershahbadi-majority Jangla Tal village, revealed that local Hindus are already discussing seizing properties of Muslims labeled as Bangladeshi infiltrators.

“When the NRC was implemented in Assam, Hindus whispered about who would claim which Muslim’s house once they were expelled,” Imam said at a tea stall overlooking the Ganges embankment in Katihar’s Amdabad. “We must prepare, but gathering old land documents to prove citizenship will be challenging.”

The Growing Acceptance of Communal Division

Recently, the Election Commission of India conducted a contentious Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of Bihar’s voter list, affecting nearly 80 million voters. This exercise imposed stringent documentation requirements, sparking accusations that it aimed to disenfranchise Muslims and other vulnerable groups in a state the BJP is eager to win.

“Kishanganj saw a tenfold surge in residential certificate applications within the first week of SIR, suggesting possible infiltration attempts,” Bihar’s Deputy Chief Minister Choudhary told reporters in July.

The final electoral roll, published on September 30, removed nearly 6 percent of voters statewide. Kishanganj, with a 70 percent Muslim population, experienced the second-highest removal rate at 9.7 percent, while Seemanchal’s overall voter deletions reached about 7.4 percent. Gopalganj, home to Lalu Prasad Yadav, Bihar’s former chief minister and leader of the BJP’s main rival, saw the highest number of removals.

During press briefings, Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar was repeatedly questioned about the number of “foreign voters” removed-a key justification for the SIR.

“Names were deleted due to deaths, ineligibility as Indian citizens, duplicate registrations, or relocation from Bihar,” he explained. The commission also stated that any party or individual could file claims or objections if eligible voters were excluded.

Akbar, a Shershahbadi Muslim from Kishanganj, confirmed his inclusion on the list. “I’m not afraid of the SIR because I have all the necessary documents,” he said. “Those targeted often prepare strong defenses.”

Academic Pushpendra believes the BJP’s portrayal of Shershahbadi Muslims as infiltrators aims to influence voters beyond Seemanchal.

“The BJP knows this tactic won’t yield much in Seemanchal due to the high Muslim population. Instead, by demonizing Seemanchal Muslims, they seek to polarize Hindus elsewhere in Bihar to secure more seats,” he told Al Jazeera.

A Climate of Fear and Doubt

The BJP’s campaign has also affected social dynamics. Muslim-run schools in Kishanganj report declining Hindu enrollment.

“Today, hardly any Hindu families send their children to Muslim-managed schools,” said Tafheem Rahman, who has operated a private school in Kishanganj for ten years.

When Rahman opened his school, Hindus made up about 16 percent of students; now, that figure has dropped to 2 percent.

“Even well-off Muslim families are withdrawing their children. This quiet withdrawal from shared educational spaces signals a dangerous normalization of communal segregation, fueled by electoral politics,” he added.

A similar pattern emerges in healthcare.

“Hindu patients hesitate to visit Muslim-run hospitals, especially those managed by Shershahbadis,” said Azad Alam, a Shershahbadi Muslim and private hospital owner in Kishanganj. “Medical associations rarely defend Muslim doctors when they face difficulties.”

Nonetheless, many Hindus in Seemanchal reject religious segregation.

“It’s wrong for a Hindu in Kishanganj to avoid Muslim doctors or schools. Kishanganj is Muslim-majority; Hindu businesses rely heavily on Muslim customers-90 percent of mine are Muslim. When I need a doctor, I seek quality, not religion,” said Ajay Kumar Choudhary, a 49-year-old washerman.

Conversely, Amrinder Baghi, a 62-year-old lawyer and longtime BJP supporter in Katihar, believes “illegal” Muslims have entered India and that the government must act.

“If someone enters my home illegally, it means either I’m weak and overpowered or strong but asleep,” Baghi told Al Jazeera.

This polarized atmosphere demoralizes the community, according to Adil Hossain, sociology professor at Azim Premji University in Bengaluru.

“Seemanchal faces developmental challenges, but the issue is being framed as a security threat through the infiltration narrative. This breeds anxiety and uncertainty, hindering people from realizing their full potential as citizens,” Hossain explained.

Back in Kishanganj, Alam remains troubled by the BJP’s campaign targeting Muslims ahead of the critical elections.

“Whenever politicians speak against Shershahbadi Muslims, we must constantly defend ourselves, denying we are infiltrators. This creates fear within our community,” he said, voice trembling as he gazed at the overcast sky.

“Being a Shershahbadi Muslim, those accusations haunt me like a persistent illness… like a ghost.”