Before dawn breaks over Lagos’s bustling Mile 12 market, a female tomato vendor is already preparing for the day ahead. Like countless women managing informal enterprises throughout Nigeria’s open-air markets, her income hinges not only on sales volume but also on the consistency of her expenses and her access to essential financial services.

This individual experience mirrors broader national trends revealing that while women constitute a significant portion of informal traders, they remain at the bottom tier of financial empowerment within this sector.

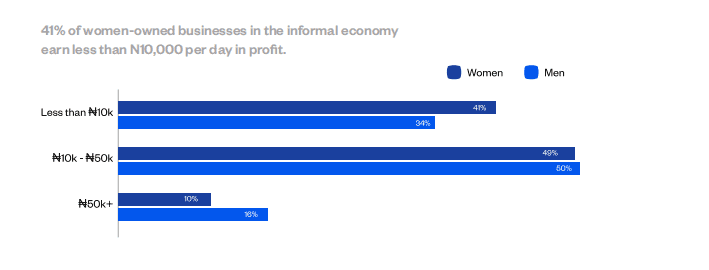

The 2025 Informal Economy Report by Moniepoint highlights that women own approximately 35% of informal businesses in Nigeria. However, 41% of these women-led ventures generate less than ₦10,000 in daily profit, compared to 34% of male-owned businesses.

Conversely, only 10% of women’s informal businesses earn over ₦50,000 per day, whereas 16% of men’s businesses surpass this threshold. This disparity underscores the tight profit margins women face, limiting their capacity to reinvest or expand their operations.

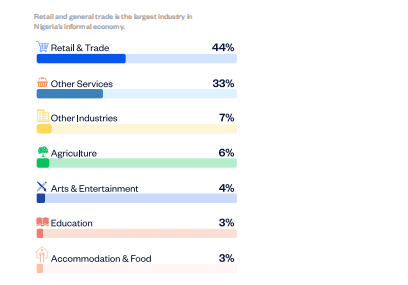

These statistics reveal a deeper narrative about Nigeria’s informal economy. Women predominantly engage in visible retail sectors-selling groceries, fresh produce, household items, and everyday necessities in local markets nationwide. Yet, ownership does not equate to financial influence.

Many women traders survive on razor-thin profits and face barriers to accessing systems that could enhance their business leverage. Their daily income is often diminished by fluctuating costs, unpredictable pricing, and unavoidable levies. Despite their prominent presence, their economic autonomy remains constrained.

Women-led informal businesses rarely secure substantial loans

Financial inequality is stark when it comes to credit access. Merely 6% of women in the informal sector have obtained loans exceeding ₦1 million, while men are twice as likely to secure such funding.

This credit gap restricts women’s ability to grow their enterprises. For instance, a female vendor in markets like Oshodi or Aba often depends on daily savings to replenish stock. When credit is available, it typically comes from informal sources such as friends, savings cooperatives, or local moneylenders, many of whom impose steep interest rates or require social collateral. Formal banking institutions remain largely inaccessible.

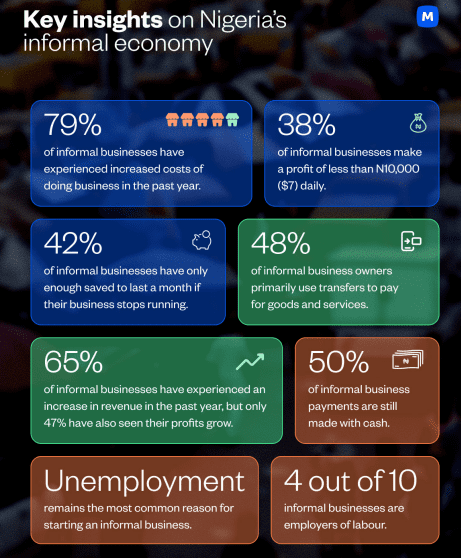

The report emphasizes that cooperative savings groups are vital lifelines for women traders. About 74% of informal business owners save regularly, with a majority of women participating in informal savings schemes like ajo and esusu.

While these savings mechanisms provide some liquidity, they lack the flexibility and scale necessary for substantial business development. For example, a woman setting aside ₦500 or ₦1,000 daily over a month might cover restocking or household costs, but such amounts rarely enable expansion or investment in improved equipment.

Another significant challenge is the daily levy many market traders must pay. Nearly half of informal businesses are subject to some form of daily tax or fee. A trader paying ₦500 each day in market dues ends up spending roughly ₦125,000 annually.

This sum often exceeds the initial capital many small-scale traders invest in inventory, meaning a large portion of their revenue is consumed by unavoidable operational expenses.

Unlike formal taxation systems that often come with documentation and potential benefits, these daily levies are typically collected informally by market associations or local authorities.

The impact is especially severe for women, who are concentrated in low-margin sectors like retail and food sales that require daily cash flow. Inflation exacerbates this strain; when prices for staples like yams or beans surge, women vendors face reduced sales and income but must still pay consistent levies.

The report further reveals that women traders are less likely to have officially registered businesses, less likely to obtain formal credit, and less likely to own the stalls they operate from.

This absence of formal assets hinders their ability to use their businesses as collateral, confining many to subsistence-level activities. It also excludes them from financial aid programs that require formal documentation or security.

Such exclusion persists despite the informal economy’s vast scale and influence. The report notes that informal businesses, especially in retail and food sectors dominated by women, generate a substantial share of Nigeria’s daily commercial transactions.

Trust issues also play a role. Many women remain wary of formal banking due to previous encounters with hidden fees, bureaucratic delays, or stringent requirements. Consequently, they prefer to rely on familiar, controllable financial arrangements.

However, this cautious approach limits their opportunities to build credit histories, access insurance products, or benefit from government-backed financial initiatives.

In conclusion, women traders are indispensable to Nigeria’s informal economy, driving daily market activity and supporting local communities. Yet, they bear disproportionate financial burdens and remain excluded from the institutional frameworks that could foster their growth and security.

0 Comments