Keir Starmer, the UK Prime Minister, embarked on his inaugural trip to India since assuming office last year, meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Mumbai, the nation’s economic hub. Accompanying Starmer was a delegation of British business and cultural figures, underscoring the visit’s emphasis on strengthening bilateral ties.

A key focus of Starmer’s visit was India’s expansive digital identity program, which has issued over 1.3 billion unique ID cards, making it the largest of its kind globally. This interest comes shortly after the UK unveiled plans for its own digital ID system, sparking debate and scrutiny.

Starmer praised India’s digital ID initiative as a “remarkable achievement” while defending the UK’s new digital ID proposal, which has faced opposition from privacy advocates. During his stay, he also engaged with Nandan Nilekani, co-founder of Infosys and the architect behind India’s digital ID infrastructure, to gain insights into the system’s development and implementation.

What Motivates the UK’s Introduction of the Digital ‘Brit Card’?

Starmer has positioned the forthcoming digital ID, dubbed the “Brit Card,” as a cornerstone in his strategy to combat illegal immigration and exploitative labor practices within the UK. He asserts that this system will enhance border security by making unauthorized employment more difficult.

Beyond immigration control, the Brit Card aims to streamline identity verification, enabling citizens to access essential services more efficiently. Starmer highlighted the everyday frustrations of managing multiple documents for routine tasks, suggesting that a unified digital ID could alleviate such inconveniences.

Despite the widespread use of ID cards across much of Western Europe, the UK has historically resisted such measures. Starmer expressed optimism that the digital format, set to become compulsory by 2029, will win public trust through its practicality.

Nevertheless, civil liberties organizations have voiced strong opposition, warning that the Brit Card could infringe on privacy rights. A petition opposing the initiative has garnered over 2.2 million signatures, describing the system as a gateway to pervasive surveillance and state control.

Understanding India’s ‘Aadhaar’ Digital Identity Framework

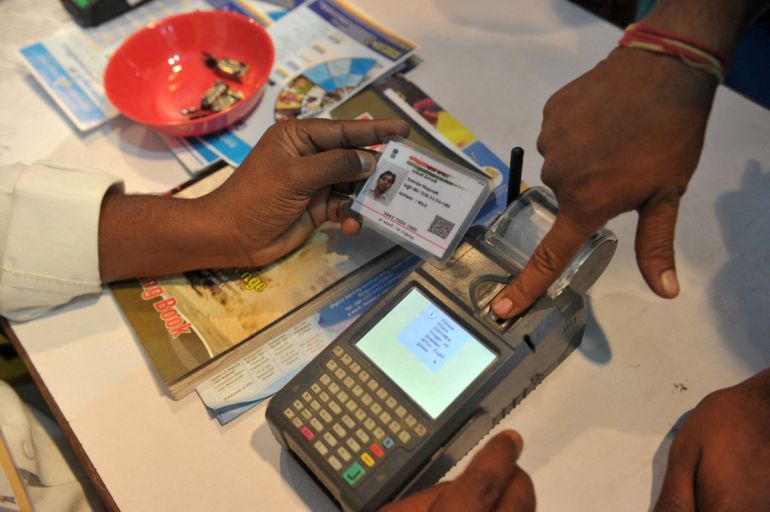

India’s Aadhaar system is far more comprehensive than the UK’s proposed digital ID. It collects biometric data including fingerprints, iris scans, photographs, addresses, and phone numbers, facilitating approximately 80 million identity verifications daily.

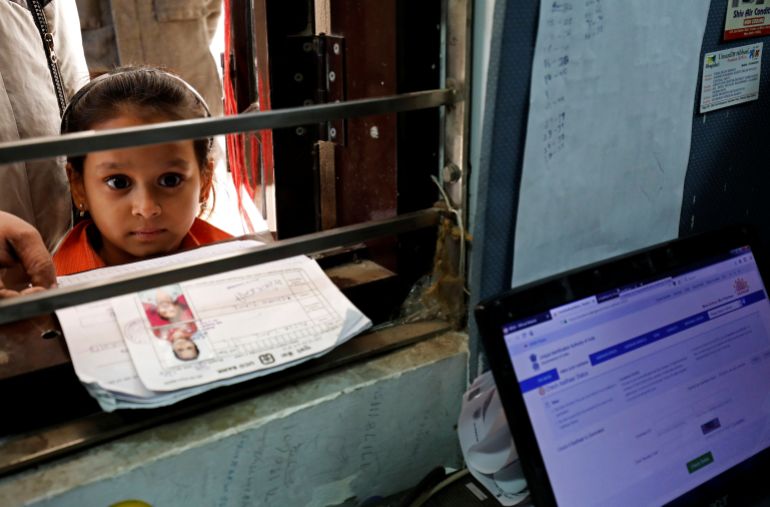

In contrast, the UK’s digital ID will focus primarily on basic identity confirmation without gathering biometric details. Aadhaar assigns a unique 12-digit number to every citizen, intended to replace numerous physical documents. Biometric data collection is mandatory for all individuals over five years old.

The system is integral to various services, such as opening bank accounts or obtaining mobile SIM cards, and has streamlined government benefit distribution by providing instant identity verification. Since its 2009 launch, over 1.3 billion Aadhaar numbers have been issued, with the government claiming significant administrative cost savings, though some experts dispute these figures.

UK officials emphasize that their goal is not to replicate Aadhaar but to learn from its implementation experience. A government spokesperson clarified that biometric data storage will not be part of the UK system, emphasizing inclusivity as a key priority in the ongoing public consultation.

The Controversies Surrounding India’s Aadhaar System

Aadhaar has been marred by multiple large-scale data breaches, exposing sensitive personal information of a vast portion of India’s population and raising serious privacy concerns. Notable leaks occurred in 2018, 2019, and 2022, with some data appearing for sale on the dark web, including information from the government’s COVID-19 vaccination portal.

In early 2025, the Indian government permitted private entities to access Aadhaar’s database for authentication, subject to government approval. This move has been met with criticism over the potential misuse of biometric and behavioral data.

Digital rights advocate Vrinda Bhandari, a Supreme Court lawyer, argues that the fundamental flaw lies in centralizing biometric data and linking it across databases, which should be avoided to protect privacy.

Public trust remains fragile; a recent survey by LocalCircles found that 87% of Indians believe their personal data has been compromised or is publicly accessible, a significant increase from 72% in 2022.

While the Unique Identification Authority of India asserts data security, the absence of a robust data protection law leaves many skeptical. Bhandari stresses the necessity of strong legal frameworks and accessible complaint mechanisms to safeguard citizens’ rights.

Moreover, Aadhaar’s reliance has sometimes adversely affected vulnerable populations, with technical glitches causing delays or denials in welfare benefits such as pensions, healthcare, and food subsidies.

India’s Supreme Court has limited Aadhaar’s use in private sectors and education but allowed its application in welfare and taxation. Recent policy changes have expanded private sector access under government oversight, though legal challenges persist.

Critics also warn that Aadhaar has fostered a surveillance infrastructure lacking adequate protections, raising alarms about civil liberties.

Global Influence of India’s Digital ID Model

India’s Aadhaar has inspired several countries to develop their own digital identity systems. Kenya’s 2019 initiative, the National Integrated Identity Management System (NIIMS), also known as Huduma Namba, was modeled closely on Aadhaar to enhance government service delivery and reduce fraud.

However, Kenyan civil society groups challenged the system over privacy and exclusion concerns, leading to a High Court injunction in 2020. Subsequently, Kenya enacted the Data Protection Act in 2021 and rebranded the system as “Maisha Namba,” promising improved data governance. Despite these reforms, legal disputes continue over data security and privacy safeguards.

Other nations, including the Philippines, Morocco, and Ethiopia, have similarly drawn from the Aadhaar blueprint for their national ID programs.

In the UK, privacy advocates remain wary of the Brit Card. Silkie Carlo, director of Big Brother Watch, cautions that the system risks eroding freedoms by creating an extensive domestic surveillance network potentially extending into areas like taxation, healthcare, and internet usage.

Responding to these fears, UK Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy assured the public that the government has no intention of implementing a “dystopian” system.

Additional Highlights from Modi and Starmer’s Mumbai Discussions

During their meeting, Modi and Starmer sought to build momentum following the free-trade agreement signed in July, which aims to double bilateral trade to $120 billion by 2030 by reducing tariffs on products such as textiles, whisky, and automobiles.

Modi emphasized the complementary strengths of India’s dynamic economy and the UK’s expertise, noting that the British delegation’s composition reflected a shared vision for deepening collaboration.

Starmer expressed confidence that the visit would secure significant investments, generating thousands of skilled jobs in emerging sectors.

The two governments announced several new initiatives, including the establishment of an India-UK connectivity and innovation center, a joint artificial intelligence development hub, and a critical minerals industry consortium to oversee responsible mining and processing.

The UK government highlighted commitments from 64 Indian companies to invest £1.3 billion ($1.73 billion) in the UK, signaling a new phase of economic partnership.

Starmer described these developments as the dawn of a “new era of collaboration” between the two nations.

Ongoing Challenges in UK-India Relations

Despite growing cooperation, some issues continue to strain UK-India relations. A significant point of divergence is their stance on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The UK, aligned with NATO, has condemned Russia and imposed sanctions, while India maintains a policy of strategic autonomy, continuing to purchase Russian oil. This difference has contributed to tensions, including US-imposed tariffs on Indian goods earlier this year.

Another sensitive topic is the presence of Sikh separatist activism in the UK, which India has repeatedly criticized, especially following the 2023 vandalism of the Indian High Commission in London.

Relations have also been complicated by a BBC documentary critical of Modi, which Indian officials labeled as “anti-India propaganda.” Additionally, diplomatic friction has intensified between India and Canada, a UK Five Eyes partner, over allegations of Indian involvement in the assassination of Sikh separatist Hardeep Singh Nijjar.

In October 2024, the UK urged India to cooperate with Canada’s investigation, affirming confidence in Canada’s judicial process. Previously, under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, the UK Labour Party had openly criticized India’s revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy, passing an emergency motion on the matter.